- Sections

- Figures

- Tables

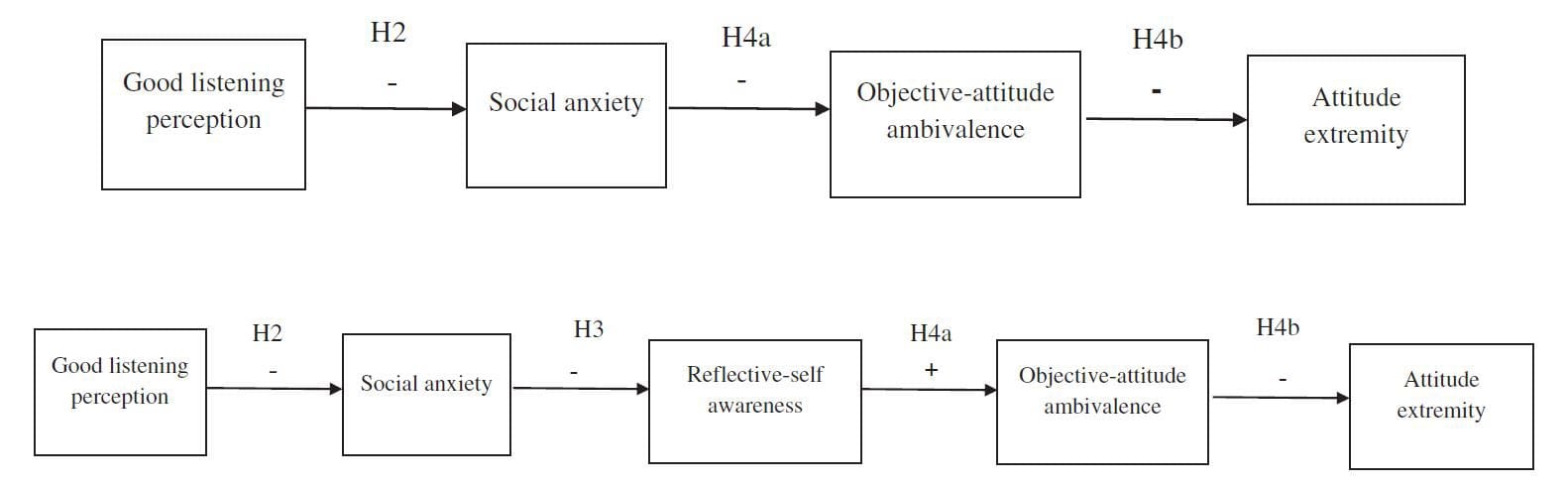

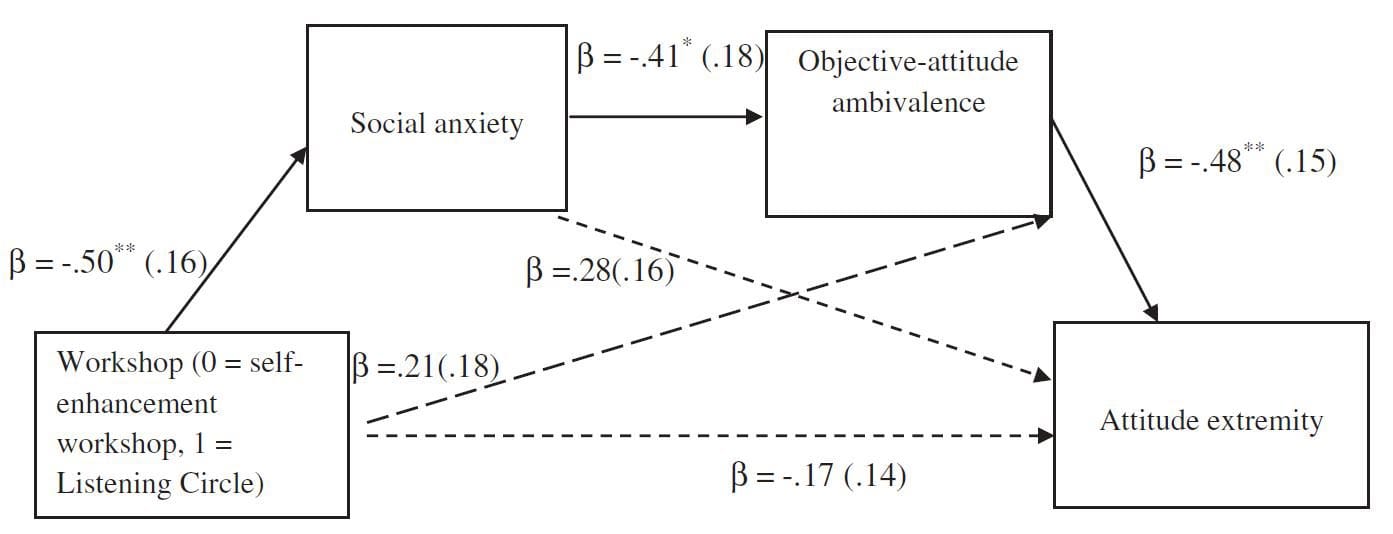

- Figure 1 (a) A path model tested in Study 1 and Study 2. (b) A path model tested in Study 3.

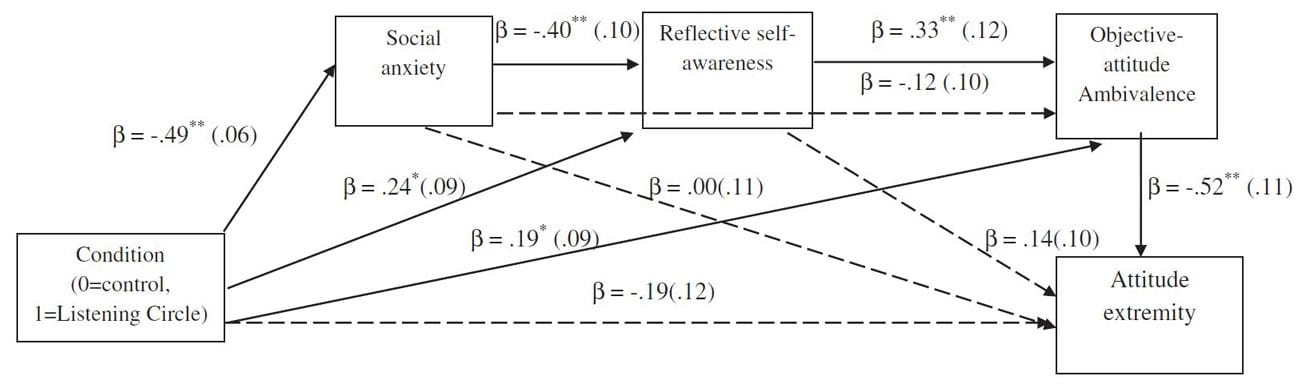

- Figure 2. Standardized estimates of the multi-step mediation model for Study 1. Standard error in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

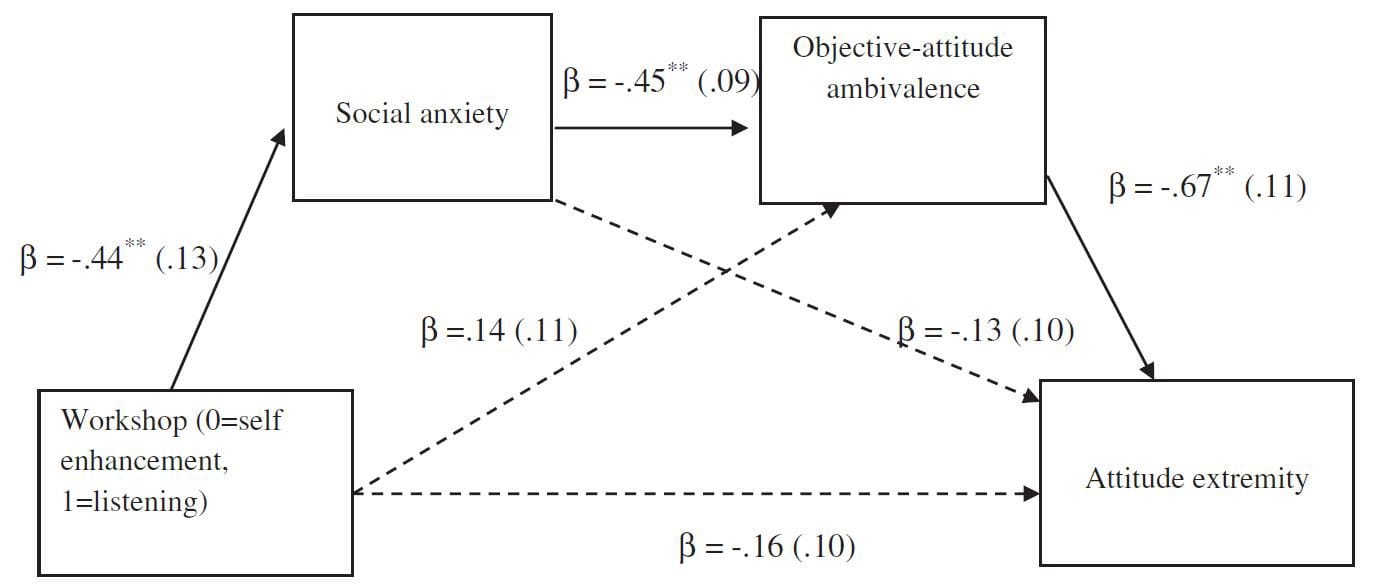

- Figure 3. Standardized estimates of the multi-step mediation model for Study 2. Standard error in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

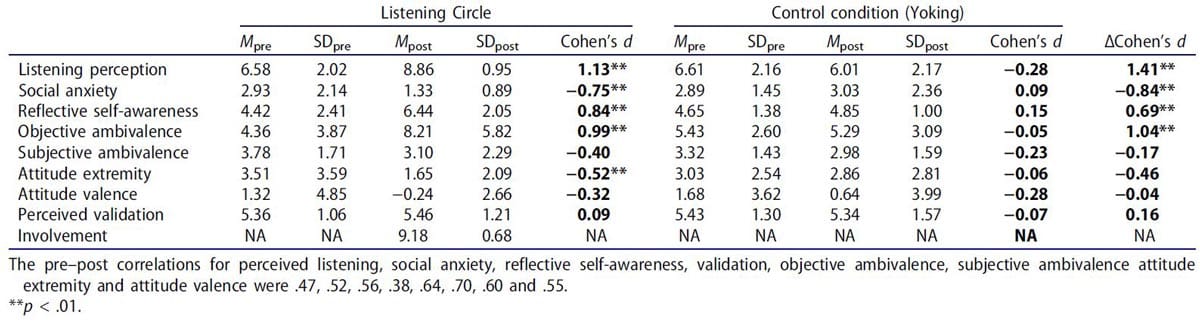

- Figure 4. Standardized estimates of the multi-step mediation model for Study 3. Standard error in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

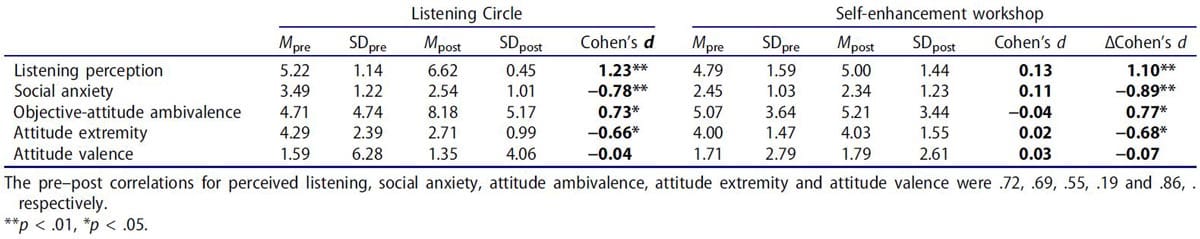

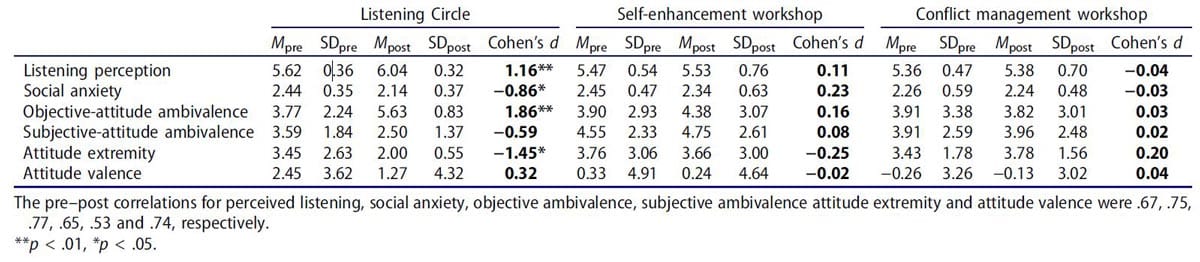

- Table 1. Study 1: Mean difference SDs and Cohen’s d for repeated measures for the pre- and post-measures by workshop.

- Table 2. Study 2: Mean difference SDs and Cohen’s d for repeated measures, for the pre- and post-measures by workshop.

- Table 3. Study 3: Mean difference SDs and Cohen’s d for repeated measures, for the pre- and post-measures by condition.

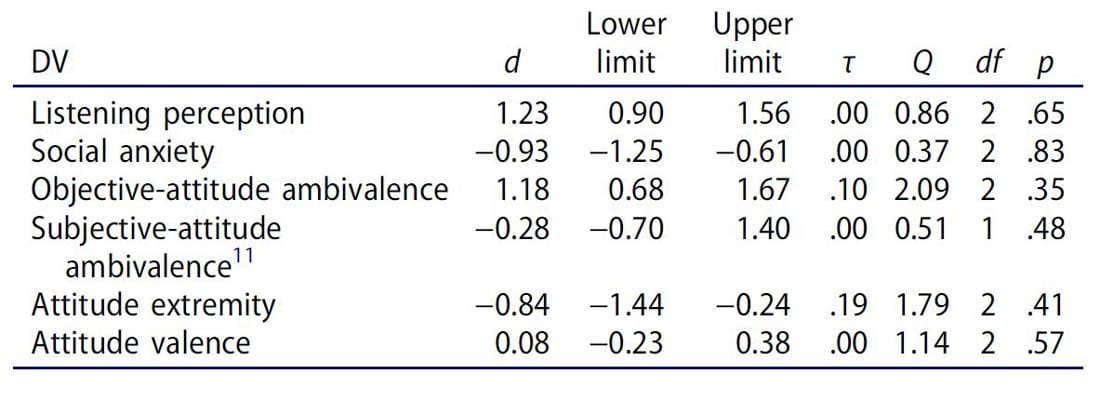

- Table 4. Mini meta-analyses testing the effects of the Listening Circle in comparison to control conditions on research variables across the three studies (N = 180).

Can holding a stick improve listening at work? The effect of Listening Circles on employees’ emotions and cognitions

Abstract

The Listening Circle is a method for improving listening in organizations. It involves people sitting in a circle where only one talks at a time. Talking turns are signalled by a talking object. Although there are several reports regarding the effectiveness of the Listening Circle, most are based on case studies, or confounded with another intervention, and do not use theory to predict the listening-induced outcomes.

We predicted that perceiving good listening decreases employees’ social anxiety, which allows them to engage in deeper introspection, as reflected by increased self-awareness. This increased self-awareness enables an acknowledgement of the pros and cons of various work-related attitudes and can lead to attitudes that are objectively more ambivalent and less extreme. Further, we hypothesized that experiencing good listening will enable speakers to accept their contradictions without the evaluative conflict usually associated with it (subjective-attitude ambivalence). In three quasi-experiments (Ns = 31, 66 and 83), we compared the effects of a Listening Circle workshop to a self-enhancement workshop (Studies 1 and 2), to a conflict management workshop (Study 2) and to employees who did not receive any train ng (Study 3), and found consistent support for the hypotheses. Our results suggest that the Listening Circle is an effective intervention that can benefit organizations.

Keywords: Listening Circle; social anxiety; reflective self-awareness; attitude ambivalence; attitude extremity

Employees spend much of their day listening to their managers, colleagues and customers. When employees listen well, they create a myriad of benefits both for themselves and for their interlocutors.

Correlational studies suggest that the perception of good listening is positively associated with job satisfaction (Brownell, 1990; Lloyd, Boer, Kluger, & Voelpel, 2015), relational satisfaction (Canlas, Miller, Busby, & Carroll, 2015; Katz & Woodin, 2002), customer loyalty (Román, 2014), objective measures of performance (Bergeron & Laroche, 2009; Levinson, Roter, Mullooly, Dull, & Frankel, 1997), job commitment (Lobdell, Sonoda, & Arnold, 1993), trust (Drollinger & Comer, 2013; Lloyd et al., 2015), voice behaviour (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2012) and organizational citizenship behaviour (Lloyd, Boer, Keller, & Voelpel, 2014; Schroeder, 2016). Subordinates who perceive their managers as good listeners attribute high levels of people leadership to them (Ames, Maissen, & Brockner, 2012; Berson & Avolio, 2004; Kluger & Zaidel, 2013). Experiencing good listening from one’s supervisor was also shown to be negatively associated with job burnout (Pines, Ben-Ari, Utasi, & Larson, 2002). Experimental data suggest that experiencing good listening increases psychological safety (Castro, Kluger, & Itzchakov, 2016) and reduces social anxiety (Itzchakov, Castro, & Kluger, 2016). Juxtaposing these benefits for speakers and listeners suggests that good listening can constitute a high-quality connection that is mutually growth fostering, enhancing and can promote the development of both dyad members as well as the bond between them (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003; Miller & Stiver, 1997).

Not surprisingly, practitioners continually point out the importance of listening skills in the workplace and recommend developing employees’ and managers’ listening skills (Brink & Costigan, 2014; Google, 2017). However, despite these recommendations and the benefits described earlier, listening has received relatively little attention in the field of management and organizational behaviour. Only a few correlational studies have focused on listening (Bergeron & Laroche, 2009; Johnson, Pearce, Tuten, & Sinclair, 2003; Román, 2014; Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2012). There is scant literature in the field of management and organizational behaviour on listening interventions. Only one study examined the effectiveness of a listening intervention (Rautalinko & Lisper, 2004). In this study, the focal construct was listening skills (as in other listening-intervention studies from other fields). However, no effect was found for the listening intervention (Rautalinko & Lisper, 2004; Study 1). Therefore, despite the notion that listening skills are essential for organizations, there is little empirical support for the effectiveness of interventions designed to develop this skill in organizations.

To respond to this need the current work had two main goals: (a) empirically test a novel listening intervention in the workplace (the Listening Circle) and (b) examine the impact of this intervention beyond the mere improvement in listening skills. More specifically, we tested whether and how the intervention- induced listening skills would manifest in changes in employees’ emotions and cognitions.

Listening is a multi-dimensional construct that includes attention, understanding and relational components. The relational features of listening include being non-judgemental, empathic and respectful (Rogers & Roethlisberger, 1991/1952). Although the construct of listening is complex, research has shown that people perceive listening holistically because different listening questionnaires designed from different perspectives have yielded either a single factor or one second-order factor (Jones, Bodie, & Hughes, 2016; Kluger & Bouskila-Yam, in press; Schroeder, 2016). Moreover, listening is a fuzzy construct that overlaps with many others (e.g., empathy, respect, responsiveness), but is not isomorphic with them. For example, studies on laypeople’s perception of the construct of respect suggest that honesty and loyalty, for example, are much more central to its definition than is listening (Frei & Shaver, 2002). Another related construct is responsiveness, which is defined as “a process by which individuals come to believe that relationship partners both attend to and react supportively to central, core-defining features of the self” (Reis, Clark, & Holmes, 2004, p. 203). Though responsiveness and listening are both forms of support, they are different in scope and in their level of abstraction. Responsiveness includes a belief that the “partner will respond supportively to expression of needs” (Reis et al., 2004, p. 203), whereas listening is about the perception of the partner’s behaviour. While responsiveness is a general and abstract term, listening is described in the literature as being associated with specific behaviours, such as asking questions (Van Quaquebeke & Felps, 2016) and paying attention (Ames et al., 2012). Therefore, following Castro et al. (2016), we define listening “as a behavior that manifests the presence of attention, comprehension, and good intention toward the speaker”. This definition is similar to a layperson’s plea of “Listen to me!” A similar approach to listening was used in research on listening and attitude extremity (Itzchakov, Kluger, & Castro, 2017).

It is worth noting that the effects of listening are a function of the speakers’ perception of listening quality, rather than the listeners’ perception of their own listening behaviour or any objective measures such as memory, or non-verbal cues. This distinction is important because previous work that examined the construct validity of listening has found no association between speakers’ perception of listening quality and listeners’ perception, r = − .14, or behavioural measures, r = − .07 (Bodie, Jones, Vickery, Hatcher, & Cannava, 2014). That is, a listener might report listening well to a speaker, remember a great deal of content, or get a good evaluation from an outside viewer, whereas the speaker does not perceive the listener to have listened appropriately. Nevertheless, only speaker’s perception of listening is likely to affect the emotional and cognitive processes within him or her.

One method of creating good listening in organizations is known as the Listening Circle paradigm. The Listening Circle, also known as the Council,(*1) involves about 10–25 people sitting in a circle with one or two trained instructors. At the beginning of the Listening Circle, the instructors explain the rules of the circle. The first rule is that only one person can talk at a time. The talking turns are signalled by a talking object, which is handed over among the participants around the circle, or placed in the centre of the circle for interested participants to pick up. The instructors invite the participants to consider four “intentions” when they participate: to listen from the heart, to talk from the heart, to talk succinctly and to talk with spontaneity. The instructors ask participants to avoid any positive or negative feedback comments to one another. They are invited to express support after a person has finished talking, by saying “Ho” or “Amen”. Finally, the instructors emphasize that speaking in the circle is not mandatory, and note that listening without speaking is also participation.(*2) That is, a participant who does not wish to speak can simply pass the talking object on without speaking (or never pick it up from the centre). The instructors drill the rules several times (usually 2–3 rounds) until participants become accustomed to the dynamic in the circle. After explaining and practising the rules, the instructors invite the group to talk about a certain topic. The topic can be specific (e.g., thoughts and feelings about one’s position at work) or general (e.g., the most meaningful experience this year).

Testing the effectiveness of the Listening Circle is important not only for organizational research but also for listening research and applying listening interventions in the field. The bulk of the experimental research on listening has relied on a distraction manipulation (Bavelas, Coates, & Johnson, 2000; Pasupathi & Hoyt, 2010; Pasupathi & Rich, 2005), or on highly trained listeners such as professional coaches or social work graduates (Itzchakov et al., 2017; Study 1 and Study 2). In contrast, the Listening Circle provides a way to test the effects of listening with a better than normal listening condition, as opposed to a distraction manipulation, which cannot be used in the field and does not require extensive resources to produce better than normal listening. That is, the Listening Circle relies on few listening-trained professionals (the organizers who convene the Listening Circles) who can create a better than normal listening experience in an entire group, as opposed to producing listening with a trained listener (e.g., a coach or a social worker), which requires pairing each participant with a trained listener. Hence, we hypothesized that:

H1: Participation in the Listening Circle will improve employees’ listening abilities, as perceived by the employees’ interlocutors.

Previous studies on listening training (Listening Circle and other methods) have not gone beyond measuring listening as a dependent variable (e.g., Aakre, Lucksted, & Browning- McNee, 2016; Johnson et al., 2003; Kennedy, 2014; Wouda & van de Wiel, 2014). By contrast, this study was aimed to test theoretically driven hypotheses regarding the effects of experiencing good listening. Specifically, we build on the perspective of Carl Rogers and on laboratory tests of his ideas (Itzchakov et al., 2017). Rogers argued that most people are eager to be listened to and really understood by the people they interact with. Yet, most people, most of the time, are not listened to well, because listeners have a natural tendency to evaluate what they hear, and this evaluation prevents good 664 G. ITZCHAKOV AND A. N. KLUGER listening (Rogers & Roethlisberger, 1991/1952). Rogers noted the huge potential of listening to heal individuals and to solve a multitude of societal problems ranging from poor leadership and management to world peace. Specifically, according to Rogers, listening restores inner communication among the parts of the self of the speaker and as a result creates a more balanced person who functions more peacefully in the world. Rogers described the effects of high-quality listening on the speaker as follows:

In this atmosphere of safety, protection, and acceptance, the firm boundaries of self-organization relax [emphasis added]. There is no longer the firm, tight gestalt which is characteristic of every organization under threat, but a looser, more uncertain configuration. He begins to explore his perceptual field more and more fully. He discovers faulty generalizations, but his self-structure is now sufficiently relaxed so that he can consider the complex and contradictory [emphasis added] experiences upon which they are based. He discovers experiences of which he has never been aware, which are deeply contradictory to the perception he has had of himself . . . (1951, p. 193)

That is, according to Rogers, experiencing good listening should free the speaker from self-presentational concerns and should thus result in reduced social anxiety (Schlenker & Leary, 1982). Hence, building on Rogers’ theory, we hypothesized that:

H2: Perception of high-quality listening reduces employees’ social anxiety.

The reduction in social anxiety facilitated by empathic and non-judgemental listening creates a psychologically safe atmosphere. In a safe atmosphere, a speaker is able to engage in deeper introspection and this experience increases selfawareness (Rogers & Roethlisberger, 1991/1952). This form of awareness corresponds to the construct of reflective selfawareness, which is defined as an attention towards the self that is motivated by curiosity or epistemic interest in the self. Reflective self-awareness is distinguished from ruminative selfawareness, which is defined as attention towards the self that is motivated by perceived threat, loss or injustice to the self (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999). Hence, we hypothesized that:

H3: Perception of high-quality listening increases employees’ reflective self-awareness by reducing social anxiety.

According to Rogers (1980) and Rogers and Roethlisberger (1991/1952), as reflected in the quote earlier, increased selfawareness should enable the speaker to acknowledge the multiplicity and inner contradictions within his or her self. That is, the speaker will become aware of contradictory thoughts and emotions regarding the issue being talked about. Such contradictions are usually suppressed because individuals have a need to appear consistent in their cognitions, beliefs and behaviour (Festinger, 1962; Heider, 1946). This notion is supported by organizational research showing that psychologically safe environments enable employees to take interpersonal risks in the form of new behaviours or speaking up, both of which create the conditions for change (Edmondson, 1999; Pratt & Barnett, 1997; Schein, 1987). When a speaker feels threatened, for example by an interlocutor who is argumentative, disrespectful or ignores the speaker (signs of poor listening), the speaker will engage in a defensive manner (Briñol, Petty, Gallardo, & DeMarree, 2007; Knowles & Linn, 2004). This process usually results in closed-mindedness and a search for information that supports the initial attitude (Liberman & Chaiken, 1992). Highquality listening should reduce such defensiveness, which in turn should enable the speaker to think in an open-minded way and become aware of viewpoints conflicting with the initial attitude. Awareness of opposite viewpoints should be manifested in objective-attitude ambivalence. Objective-attitude ambivalence is defined as simultaneous oppositional positive and negative orientations towards an object and includes cognition or emotion (Ashforth, Rogers, Pratt, & Pradies, 2014; Fabrigar, MacDonald, & Wegener, 2005; Kaplan, 1972). For example, a person may like the taste of an ice cream but hate the calories that come with it.

The idea that the perception of good listening increases objective-attitude ambivalence was repeatedly supported in four laboratory experiments where listening was manipulated either by employing trained listeners or distraction (Itzchakov et al., 2017). Hence, to generalize these findings to employees in a field setting we hypothesized that:

H4a: Perception of high-quality listening increases employees’ objective-attitude ambivalence by decreasing social anxiety.

A common assumption in the attitude literature is that objective ambivalence leads to subjective-attitude ambivalence (e.g., DeMarree, Wheeler, Briñol, & Petty, 2014; Maio, Bell, & Esses, 1996; Van Harreveld, Nohlen, & Schneider, 2015), which is defined as an experience of evaluative conflict towards an attitude object, and includes feeling conflicted, indecisive, being torn and having mixed feelings with regard to the attitude object (Priester & Petty, 1996). However, based on earlier findings of Itzchakov et al. (2017), we hypothesized that subjective-attitude ambivalence would be less likely to occur when an attitude is expressed in front of a good listener. This is because a good listener conveys acceptance of any point of view made by the speaker, even if inconsistent. Under such conditions, speakers should be willing to accept and tolerate their contradictions as legitimate without feeling discomfort. Crucially, a listener does not necessarily have to agree with the speaker’s attitude but rather should convey a feeling of acceptance to the speaker. When individuals feel accepted intrinsically for who they are, they express less defensive biases when forming evaluations than when they feel that their acceptance is contingent, in particular within the context of a complex presentation of the self (Schimel, Arndt, Pyszczynski, & Greenberg, 2001). Thus,

H4b: Experiencing good listening will enable speakers to tolerate their inconsistencies, thereby moderating the association between objective- and subjective-attitude ambivalence.

Again based on earlier findings, we hypothesized that the increase in the speakers’ objective-attitude ambivalence should result in decreased attitude extremity, which is defined as the extent to which the attitude deviates from neutrality (Krosnick & Petty, 1995). Attitude extremity is negatively EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF WORK AND ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY 665 associated with objective ambivalence (Krosnick, Boninger, Chuang, Berent, & Carnot, 1993; Lee & Chan, 2009), but the theoretical correlation between these constructs is only approximately .50, such that the two constructs are not isomorphic. Perception of high-quality listening was found to reduce attitude extremity in conflict situations (Bruneau & Saxe, 2012). Possessing extreme attitudes is used as selfdefence in threatening situations (Maio & Haddock, 2010). For example, in argumentative situations individuals may feel threatened by the loss of freedom to have an attitude (Brehm, 1972) and are likely to bolster their initial attitude (Heller, Pallak, & Picek, 1973). Such process should not occur when an attitude is expressed in the presence of an empathic and non-judgemental listener. Hence, we hypothesized that

H4c: Perception of high-quality listening reduces employees’ attitude extremity by increasing objective-attitude ambivalence.

In sum, we sought not only to test whether the Listening Circle improves listening in the workplace, but also to offer a more ecologically valid test of Rogers’ hypotheses. Formally, we tested a multi-step mediation model where participation in the Listening Circle improves employees’ listening ability. The improvement in listening ability makes employees’ interlocutors (other employees when in the role of speakers) less socially anxious and more self-aware when they discuss work-related issues. This process should make the speakers’ attitudes more complex and less extreme (see Figure 1(a,b)).

Figure 1 (a) A path model tested in Study 1 and Study 2. (b) A path model tested in Study 3.

Overview of studies

We conducted three intervention studies (quasi-experiments). In the first two quasi-experiments, participants were employees of an Israeli municipality employing over 4000 people. The management of the municipality sends its employees, as a matter of routine, to take part in various workshops designed to improve soft skills, one of which is the Listening Circle.

We were able to evaluate employees in these workshops as well as in control workshops that were highly similar in scope, but did not train participants in listening. In Study 3, we tested the model on two different samples: employees of a large hightech company, and high school teachers. When we collected data at the high-tech company, we used yoking for control. Specifically, we asked the human resource department of the company to pair each participant in the Listening Circle with an employee with similar gender, seniority, role and duration of employment in the company. We compared the Listening Circle workshop to a control group composed of yoked employees who did not participate in any training.

Study 1

Method:

The participants were 31 municipality employees, Mage = 49.6, SD = 8.6, from various divisions. We had no control over the sample size (see procedure below); however, if we assume that the correlation between pretest measure and posttest measure is .50, a sample size of 27 participants has a power of .80 to detect a moderate effect size, d = 0.50, in a pairedsample design.

The municipality’s human resource management department assigned its workers to workshops. At the time we collected data, managers could allocate their subordinates to participate either in a listening-circle workshop, n = 16, or in a confidenceenhancement workshop, n = 15. The allocation was at the discretion of the senior managers; hence our design was quasi-experimental. The managers allocated employees of an entire department to one workshop or another based on dates that fit their departments’ schedule; that is, when most employees could attend. Both workshops were 6 h long and included two breaks, one short break (15 min) and one lunch break (45 min). Upon arrival at the workshops, participants were asked to recall a significant experience they had had with a colleague and completed pretest questionnaires.

Participants in the Listening Circle workshop were trained in the benefits of attentive and empathic listening, and were given practical tools for its implementation in daily interactions in the workplace. Specifically, two instructors arranged the chairs in one circle and gave background on the history and development of the Listening Circle paradigm (Bommelje, 2012) and its rules. Then, participants were asked to introduce themselves.(*3) Each participant who spoke held a “talking object”, which indicated who had the permission to speak. Afterwards, participants shared the significant experience they had had with a colleague that they referred to in the pre-workshop questionnaire, while their colleagues listened without interruptions. We instructed the participants to choose an event dealing with a colleague who was not present at the workshop. We also asked participants not to mention the names of their colleagues they were talking about.(*4) For example, a social worker shared the following experience:

About three months ago, I asked my colleague, with whom I have worked for many years, to replace me on a home visit because I had to pick up my child early from school because he got hurt. My colleague said she couldn’t do that because she had very important work to finish and the deadline was the next day. Eventually I found another social worker to replace me, but I have been angry with her (the colleague who refused to substitute her) ever since. I act as though everything is fine between us but the truth is that this is not true. I think however, that she realizes that I act differently towards her since that incident, but we have not talked about it.(*5)

This procedure was repeated so that (a) each speaker had the opportunity to elaborate on the experience and (b) the other participants practised how to listen attentively without interrupting.

The self-enhancement workshop combined a lecture and training in different thinking strategies and applied activities. The goal of the workshop was to impart skills that enable selfconfidence enhancement, coping with pressure and making quick decisions when time is running out. Specifically, participants (a) received both theoretical and practical tools, (b) learned self-control techniques, alongside with the experience of their impact on decisions and behaviour of others and (c) learned and practised making wise and rational decisions under time pressure. Participants in the self-enhancement workshop did not talk about the event they reported in the pre-workshop questionnaire.

Immediately after the workshops ended, all participants filled out the posttest questionnaires. Note that in this study as in the next studies, we used the same measure for each variable in the pre- and post-workshop measurement.

Measures:

We used the team-listening-environment scale (TLE; Johnston, Reed, & Lawrence, 2011) as a manipulation check on the effectiveness of the Listening Circle. This scale consists of six items, rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale anchored at 1 = completely disagree and 7 = completely agree. For the pre-training measure, we adapted items to fit daily interactions in the work place (e.g., “My work colleagues genuinely want to hear my point of view”, “My work colleagues show me that they understand what I said”, “My work colleagues pay attention to me”); for the post-training measure, we adapted the items to fit the workshop (e.g., “The other workshop members genuinely wanted to hear my point of view”), αpre = .95, αpost = .93.

We adapted the 7-item State Social Anxiety scale (STAI; Kashdan & Steger, 2006) to fit social interactions with colleagues (e.g., “I was worried about what my colleagues thought of me”, “I was afraid that my work colleagues did not approve of me”), αpre = .92, αpre = .94.

We examined objective-attitude ambivalence with a split semantic differential scale, which included the following items, “Ignoring your negative thoughts and feelings about the experience with the colleague, and considering only your positive thoughts and feelings, how positive is your attitude”, where 0 = not at all, and 10 = completely, and, “Ignoring your positive thoughts and feelings about the experience with the colleague, and considering only your negative thoughts and feelings, how negative is your attitude” (0 = not at all, −10 = completely.) We calculated complexity according to Kaplan’s (1972) formula: Positive + |negative| − |(positive + negative)|. The scale ranged from 0 to 20. Higher scores indicated more ambivalent attitudes.

We calculated attitude extremity by the formula: |positive + negative| (Kaplan, 1972). The scale ranged from 0 to 10. Higher scores indicated a more extreme attitude.

Attitude valence reflects the extent to which an attitude is positive or negative. We calculated the valence score according to Kaplan as (positive + negative).

Note that although objective-attitude ambivalence and extremity are mathematically correlated, when using Kaplan’s formulas, an increase in objective ambivalence does not necessarily entail a decrease in extremity or vice versa. The same objective ambivalence may reflect different levels of extremity, and the same level of extremity may reflect two levels of objective ambivalence. For example, if a person assigns a −3 to a negative item and a 3 to a positive item, the objective-attitude ambivalence is 6 whereas the attitude extremity is 0. If a person assigns a −9 to a negative item and a 9 to a positive item, the objective-attitude ambivalence is 18 whereas the attitude extremity is 0. Similarly, an extremity score of 4 may reflect both a positive score of 6, and a negative score of −2 or a positive score of 7 and a negative score of −3. However, in the former case, objective-attitude ambivalence will be 4 and in the latter it will be 6.

Results and discussion

Table 1 presents the mean difference and SDs for all dependent variables by time and type of workshop. To test our hypotheses, we ran a mixed ANOVA, with measurement time as the withinparticipant factor, and condition as the between-participant factor.(*6) The increase in perceived listening among attendees in the Listening Circle wasmuch higher than the change in listening among attendees in the self-enhancement workshop, F (1,29) = 16.54, p < .001, η2 p = .51, suggesting that the Listening Circle is a valid intervention to increase listening, in support of H1.

The listening-workshop attendees reported a stronger (a) decrease in social anxiety than attendees in the self-enhancement workshop, F(1, 29) = 6.04, p = .02, η2 p = .17, (b) increase in objective-attitude ambivalence, F(1, 29) = 5.48, p = .03, η2 p = .16 and (c) decrease in attitude extremity, F(1, 29) = 4.57, p = .04, η2 p = .13, all in support of H2. As expected, there was no significant difference between the workshops on attitude valence, F (1, 29) = 0.03, p = .87, η2 p = .00. Given our quasi-experimental design, prior to testing our hypotheses, we tested whether the groups had similar scores on all pretest measures. The pretest scores of the attendees in the Listening Circle were similar to the pretest scores of the attendees in the self-enhancement workshop on all measures: listening experience, social anxiety, objective- attitude ambivalence, attitude extremity and attitude valence, ts(29) = 0.94, 2.25, 1.41, 0.40 and −0.07, ps = .35, .11, .17, .69 and .95, respectively.

Table 1. Study 1: Mean difference SDs and Cohen’s d for repeated measures for the pre- and post-measures by workshop.

In all studies, we tested our model using bootstrapping procedures as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). The test was based on the 95% CI of 5000 bootstrapped samples. For each dependent variable, we computed the residual score by regressing the pretest score on the posttest score. For example, the dependent variable of listening was the posttest score residualized from the pretest score.

As can be seen in Figure 2, the indirect effect of the Listening Circle workshop via social anxiety on objective-attitude ambivalence was significant, β = .20, 95% CI [.05, .48] whereas the direct effect was not, β = .21, 95% CI [−.17, .58], consistent with full mediation. Moreover, the indirect effect of the Listening Circle, via social anxiety and objective-attitude ambivalence on attitude extremity, was also significant, β = −.10, 95% CI [−.25, −.02], whereas the direct effect was not, β = −.17, 95% CI [−.47, .13], also consistent with full mediation.(*7)

In sum, Study 1 provided support for the hypotheses. The Listening Circle improved the listening quality of the employees and had an impact on their emotions and cognitions. However, potential additional processes might have occurred between the pre and post-measurements that could explain our findings. That is, when individuals merely talk about a meaningful experience, regardless of the listening quality of the interlocutor, they may become aware of cognitions that contradict the initial attitude. However, Study 1 could not test this explanation because only Listening Circle attendees discussed their meaningful experience between the pretest and posttest measurements. Moreover, in Study 1 all attendees discussed their meaningful event in the circle. Hence, it is possible that the act of listening to other people describe their meaningful experience could have increased the attendees’ ambivalence about their own meaningful experience. In other words, hearing other people’s experiences could make individuals realize new pros and cons of their own experience. Finally, in Study 1 we did not measure subjective- attitude ambivalence. Study 2 was designed to test the shortcomings of Study 1, and specifically to test H3.

Figure 2. Standardized estimates of the multi-step mediation model for Study 1. Standard error in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

Study 2

Method:

Participants were 66 city-hall workers, Mage = 43.1, SD = 9.8, 57% women. This sample size, with the average pretest–posttest correlation of Study 1 (.60; see Table 1), has a power of 99.4% to detect a moderate effect size, Cohen’s f = .25.

Municipality workers attended one of three workshops designed to improve their work-related skills: (a) a Listening Circle, n = 22, (b) a self-enhancement workshop, n = 20 and (c) a conflict management workshop, n = 24. None of the attendees had participated in Study 1. Different instructors were in charge of the Listening Circle and self-enhancement workshops. As in Study 1, the assignment of workers to workshops was done by the human resource management department of the municipality, by considering workers’ schedule and workload constraints, thus rendering our design quasi-experimental. Each workshop included workers from a variety of different roles and departments (e.g., sanitation engineers, kindergarten teachers, tax department workers, secretaries, etc.). All workshops took place between 9:00 am and 3:00 pm, as in Study 1.

At the beginning of each workshop, we randomly assigned participants to speaker–listener dyads. We instructed speakers to talk about their attitude towards their supervisor for 10 min, and listeners to: “listen as you listen at your best”. Then, we instructed them to switch roles. Afterwards, participants completed the pretest questionnaire.

The procedures for the Listening Circle and self-enhancement workshop were the same as in Study 1. However, unlike in Study 1 participants in the Listening Circle talked about topics such as their hobbies, families and where they wanted to see themselves in 5 years.

Attendees in the conflict management were learning how to negotiate their own disputes. Attendees learned both how to negotiate with others to create more durable and meaningful resolutions, and how to communicate more effectively with others to decrease disputes. They also practised handling emotionally charged situations, and cognitive strategies to look at a given situation from different perspectives.

At the end of each workshop, we assigned participants again to different dyads than in the pre-workshop. We asked speakers to talk again about their attitude towards their supervisor. As inthe pre-workshop session, we switched roles after 10 min. Afterwards participants responded to the posttest questionnaire. The topic of attitude towards the supervisor was not discussed in the Listening Circle, or in any other group.

We used the same measures as in Study 1, tailored to the specific interactions and topics in this study: perceived listening, αpre = .87, αpost = .89; social anxiety: αpre = .78, αpost = .83; and the three measures of attitudes pertaining to attitude towards the supervisor, that is, objective-attitude ambivalence, attitude extremity and attitude valence.

We assessed subjective-attitude ambivalence by directly asking participants to report, using 11-point Likert-type scale, 0 = not at all, 10 = very much, the extent to which they felt indecision, confusion or conflict regarding their attitude (Priester & Petty, 1996), αpre = .90, αpost = .87.

Results and discussion

Table 2 presents the mean difference and SDs for all DVs by time and type of workshop. To test our hypotheses, we ran a mixed ANOVA, with measurement time as the within-participant factor, and condition as the between-participant factor. To assess the direction of the interaction effects, we calculated Cohen’s d statistics for differences in change (Morris & DeShon, 2002). The change in perceived listening among attendees in the Listening Circle was much higher than the change in listening among attendees in the self-enhancement and conflict management workshops, ds = 1.16, 0.91, respectively, ps < 0.01, suggesting, again, that the Listening Circle is a valid intervention to increase listening, supporting H1.

Attendees in the Listening Circle, compared to attendees in the self enhancement and conflict management workshops, reported a stronger (a) decrease in social anxiety, ds = −0.80, −0.83, respectively, ps < 0.01, (b) increase in objective-attitude ambivalence, ds = 0.66, 0.79, respectively, p = 0.01, p < .01, respectively, (c) decrease in subjective-attitude ambivalence, ds = −0.67, −0.61, respectively, p = 0.01, p = .03, (d) decrease in attitude extremity, ds = −0.58, −0.76, p = 0.04, p < .01. There was no difference in the change in attitude valence between conditions, F(2, 63) = 2.20, p = .12, η2 p = .03. As in Study 1, the pretest scores of attendees in the different workshops were similar on all measures: listening experience, social anxiety, objective-attitude ambivalence, subjective-attitude ambivalence, attitude extremity and attitude valence, Fs(2, 63) = 2.21, 0.95, 0.34, 0.95 0.21, 2.32, ps = .12, .38, .97, 0.39 .81, .11, respectively. Finally, there was no difference between the control groups on any of the DVs. Hence, we averaged the DV scores across to both control groups to conduct the mediation analysis.

We then examined whether listening experience moderated the association between objective-and-subjective attitude ambivalence. First, we regressed the posttest scores of objective-and-subjective attitude ambivalence on their pretest score and used the residual scores. Then, we regressed the residual of subjective-attitude ambivalence on (a) workshop type (1 = Listening Circle 0 = control conditions), (b) objective-attitude ambivalence (residualized) and (c) their interaction term. The interaction term was significant, β = −.48, p < .01. That is, objective-attitude ambivalence predicted subjective-attitude ambivalence in the control conditions but not in the Listening Circle. Specifically, the correlation between objective-and-subjective attitude ambivalence in the Listening Circle was not significant, r = −.19, p = .39, whereas the correlations in the self-enhancement and conflict management workshops were significant, positive and similar, rs = .52, .60, ps <.01. Hence, we averaged the correlations in the control conditions. The correlations in the Listening Circle workshop and control conditions were significantly different from each other, according to a Hotelling t test for correlated correlation, Z = −2.97, p < .01. This result lends weight to H3.

Table 2. Study 2: Mean difference SDs and Cohen’s d for repeated measures, for the pre- and post-measures by workshop.

For each variable, we residualized the posttest score from the pretest score and used these residual scores in a mediation analysis, as in Study 1. As can be seen in Figure 3, the indirect effect of the Listening Circle workshop via social anxiety on objective-attitude ambivalence was significant, β = .21, 95% CI [.10 .33], whereas the direct effect was not significant, β = .14, 95% CI [−.07, .36], consistent with full mediation. Moreover, the indirect effect of the Listening Circle, via social anxiety and objective-attitude ambivalence, on attitude extremity was significant, β = −.14, 95% CI [−.25, −.07], whereas the direct effect not significant, β = −.16, 95% CI [−.35, .03], also consistent with full mediation.

In sum, Study 2 replicated the results of Study 1 using a design including two quasi-control groups, and a different attitude topic. Attendees in all workshops discussed their attitude both in the beginning and at the end of the workshop, which refutes the counter claim that the listening-induced effects on employees’ attitudes were the result of repeatedly expressing the attitude. However, despite the consistent support for the research hypotheses, several unanswered questions remain. First, in both Study 1 and Study 2, we did not measure reflective self-awareness; hence, H3 could not be tested. Second, it is possible that the effects obtained in both studies were not a result of good listening perception but rather because people who perceive good listening on the part of their interlocutors felt validated with regard to their opinions, which in turn affected their attitude constructs. Moreover, one of the principles of the Listening Circle is not to coerce speaking (cf. the introduction). Hence, another question is how, and whether, the degree of involvement in the Listening Circle affects attitude structure. An association between involvement in the circle and objective ambivalence might suggest that the attitudes of participants in the circle become more objectively ambivalent and less extreme simply because they heard a myriad of different opinions and perspectives, and not because of a good post-circle listening experience. To provide answers to these questions, we conducted Study 3.

Figure 3. Standardized estimates of the multi-step mediation model for Study 2. Standard error in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

Study 3

Study 3 had several goals. The first was to test reflective selfawareness and the perception of validation as mediators of objective ambivalence. The second was to test involvement in the Listening Circle as an alternative explanation for our results. The final goal was to generalize the findings of Studies 1 and 2 to employees in the private sector.

Method:

We recruited 83 participants, Mage = 36.17, SD = 7.18, 51.8% female. This sample size, with the average pretest–posttest correlation of Study 1 and Study 2 (.64; see Tables 1 and 2), has a power of above 99.9% to detect a moderate effect size, Cohen’s f = .25.

The procedure mirrored that of Study 2. We collected data in two Listening Circle workshops, held on different dates. One workshop was given at a large high-tech company (n = 39), and one workshop was given at a high school to teachers (n = 16). At the high-tech company, the control group was made up of employees who did not participate in the Listening Circle workshop (n = 28). These participants were recruited, with the help of the human resource department, by yoking. That is, they were similar in age, years in the organization, seniority and role, to the 28 participants in the Listening Circle workshop. Participants in the control group received no training. They were randomly assigned to dyads before the Listening Circle began, went back to work and were randomly assigned again to different dyads at the end of the Listening Circle.(*8)

As in Study 2, participants were randomly assigned to dyads before the Listening Circle. Speakers were given instructions to talk about a meaningful experience at the workplace for 6 min, while listeners were instructed to “listen as you listen at your best”. Afterwards, participants switched roles and answered the pre-workshop questionnaires. After the Listening Circles, the employees were randomly assigned to different dyads. Speakers were instructed to talk about another meaningful experience at work, different from the experience they shared in the pre-workshop conversation, while listeners received the same instructions. Finally, participants answered the post-workshop questionnaires and were de-briefed. Note that participants in the Listening Circle were only assigned to dyads with other attendees of the circle, and employees in the control group were only randomly assigned to participants in the control group.

All items were anchored on an 11-point Likert-type scale (0 = strongly disagree,10 = strongly agree). We used the same measures as in Study 2: perceived listening, αpre = .95, αpost = .98; social anxiety: αpre = .89, αpost = .91, subjective-attitude ambivalence, αpre = .96, αpost = .85; and a pair of split semantic differential, examining the positive and negative thoughts and cognitions towards the meaningful experience separately, were used to calculate objective-attitude ambivalence, attitude extremity and attitude valence.

We adapted six items from the reflective self-awareness scale (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999) that were appropriate for a stateself- awareness measure in the conversation context (e.g., “When I was talking, I felt I explored my inner self”), using an 11-Likert-type scale, αpre = .94, αpost = .92.

We wrote three items to measure the extent to which speakers felt that the listeners validated the attitude they expressed (“I think the listener agreed with the attitude I expressed towards the event”, “If the listener could have expressed his/her attitude, he/she would have expressed a similar attitude to mine”, “I think the listener’s attitude was similar to mine”), αpre = .85, αpost = .88.

We wrote four items to measure the extent to which the attendees in the Listening Circle felt involved (“I actively participated in the Listening Circle”, “I felt involved in the Listening Circle”, “I felt a sense of belongingness with the rest of the participants in the circle”, “I spoke when my turn came during the circle”), α = .81.

Results and discussion

Table 3 presents the mean difference and SDs for all DVs by time and condition. As in the previous studies, we ran a mixed ANOVA, with measurement time as the within-participant factor and condition as the between-participant factor. The increase in perceived listening among attendees in the Listening Circle was much higher than the change in the control condition, F(1,81) = 23.93, p < .001, η2 p = .23.

The listening-workshop attendees(*9) reported a stronger decrease in social anxiety than attendees in the control group, F(1, 81) = 9.52, p = .003, η2 p = .11, and an increase in reflective self-awareness and objective-attitude ambivalence, Fs(1, 81) = 7.20, 6.05, ps = .009, .02, η2 p = .08, .07, respectively. Moreover, attendees in the Listening Circle workshop reported a stronger decrease in attitude extremity, F(1, 81) = 4.17, p = .04, η2 p = .05. There were no significant differences between the attendees in the different conditions on subjective- attitude ambivalence, attitude valence or perceived validation, Fs(1, 81) = 0.38, 0.20, 0.25, ps = .54, .66, .62, respectively, η2 p = .00. The pretest scores of the attendees in the Listening Circle were similar to the pretest scores in the control group across all measures: listening perception, social anxiety, reflective self-awareness, perceived validation, objective- attitude ambivalence, subjective-attitude ambivalence, attitude extremity and attitude valence, ts(81) = −0.07, 0.09, −0.55, −0.27, −1.31, 1.29, 0.70, −0.37 ps ≥.19.

In addition, the interaction term of objective ambivalence (residualized) × condition (0 = control, 1 = Listening Circle) was significant in predicting subjective ambivalence (residualized), β = −.56, p = .03. That is, objective-attitude ambivalence predicted subjective-attitude ambivalence in the control condition but not in the Listening Circle. Specifically, the correlation between the residualized scores of objective-andsubjective attitude ambivalence in the Listening Circle was not significant, r = −.18, p = .18, but significant in the control condition, r = .49, p = .008. A Hotelling t test for correlated correlations indicated that these correlations differed significantly, Z = −2.95, p = .003 and replicated Study 2 in support of H4b.

Finally, we examined the correlations between involvement in the Listening Circle and the residualized changes of the variables in the model. There was no significant correlation between involvement and listening perception, social anxiety, objective ambivalence or attitude extremity, r(54)s = .03, −.10, −.03, −.14, .05, respectively, ps ≥.32.

Table 3. Study 3: Mean difference SDs and Cohen’s d for repeated measures, for the pre- and post-measures by condition.

We used the same approach to mediation as in Studies 1 and 2 (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). As can be seen in Figure 4, the indirect effect of the Listening Circle, via social anxiety, reflective self-awareness and objective ambivalence, was significant, β = −.14, 95% CI [−.31, −.03], whereas the direct effect was not significant, β = −.19, 95% CI [−.41, .05], consistent with full mediation.

In sum, Study 3 served to generalize our results from municipal workers to high-tech workers and teachers. The results refute several alternative explanations. First, the null effect for perceived validation indicates that the listeninginduced changes in emotions and cognitions cannot be attributed to speakers feeling that listeners agree with their attitudes. Second, the lack of correlations between involvement in the Listening Circle and the attitude constructs suggests that it is more likely that the attitude became more objectively ambivalent and less extreme due to perception of good interlocutor listening in the dyadic interaction than to hearing a myriad of opinions and perspectives during the circle. The refutation of these alternative explanations bolsters the role of listening perception as the mechanism that induced the hypothesized emotional and cognitive changes. As can be seen in Table 3, there was a ceiling effect on involvement in the Listening Circles, which indicates that the vast majority of participants felt highly involved in the Circle.

Figure 4. Standardized estimates of the multi-step mediation model for Study 3. Standard error in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

Meta-analysis

To assess the effect size of the Listening Circle workshop on the research variables, we ran a random-effect meta-analysis using the data from the three studies (for the need to conduct a meta-analysis on one’s own studies, see Goh, Hall, & Rosenthal, 2016). We entered the effect size of each study and submitted it to a SPSS macro that calculates Cohen’s d for repeated measures (Field & Gillett, 2010). As can be seen in Table 4, the Listening Circle induced powerful effects on listening perception, social anxiety, objective ambivalence and attitude extremity, all of which exceeded Cohen’s d of .80 that is considered the threshold for strong effects. There was no significant effect of the Listening Circle on subjective ambivalence(*10) or attitude valence. There was no heterogeneity between studies, Q(2) ≤2.09, p ≥ .35. This analysis could suggest that the differences in effect sizes across the studies stemmed solely from sampling error, but this Q-statistic test is not sufficiently powerful to rule out the possibility that some Listening Circles were more effective than others (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009).

Table 4. Mini meta-analyses testing the effects of the Listening Circle in comparison to control conditions on research variables across the three studies (N = 180).

General discussion

In three quasi-experiments, we consistently showed that the Listening Circle increased employees’ listening behaviour, and that this improvement in listening was consequential for both affect and cognition. Using various attitude topics and workers from both the public and private sector, we obtained evidence that participation in a Listening Circle reduced social anxiety and created attitudes that are more complex and less extreme. Although our studies were quasi-experimental, their pretest–posttest comparison acrossmultiple groups removed several threats to internal validity, and their validity was bolstered by providing a replication for well-controlled laboratory studies (Itzchakov et al., 2017).

Our research differs from previous studies on listening trainings in several ways. First, most training programmes allocate much of the time to teaching theories about listening and its benefits (e.g., Davidson & Versluys, 1999; Lawrence et al., 2016; McNaughton, Hamlin, McCarthy, Head-Reeves, & Schreiner, 2008). The Listening Circle, on the other hand, is aimed at creating conditions such as sitting in a circle and holding a talking object, that facilitate high-quality listening. In the Listening Circle training, less time is devoted to lecturing to trainees that listening is good and beneficial, and more time is spent on practising listening skills under facilitating conditions. Second, most research on listening training has focused on examining how training affects the trainees’ listening skills (e.g., De Lucio, López, López, Hesse, & Vaz, 2000; Graybill, 1986; Rautalinko & Lisper, 2004). Our studies went beyond this by examining listening-induced emotional and cognitive consequences. Specifically, we tested theory-driven hypotheses (Rogers & Roethlisberger, 1991/1952) that to date have only been tested in the laboratory (Itzchakov et al., 2017).(*12) Our research provides some of the first quantitative evidence that Rogers’ ideas also apply to workplace settings. Thus, employees who experience high-quality listening are likely to become more relaxed (less socially anxious), which in turn should enable them to delve deeper into their thoughts (increased reflective self-awareness) and adopt more complex attitudes in a way that is tolerable to themselves and others. Finally, this process should result in less extreme work-related attitudes.

Across all studies, we found a strong effect of the Listening Circle on listening experience. The effect sizes were not significantly different from effects of listening manipulations in the laboratory (Itzchakov et al., 2017). However, these findings were obtained by comparing good and poor listening, which is useful for demonstrating the theoretical mechanism, but cannot be used in the field (a manipulation that reduces listening). In contrast, here we found similar theoretically predicted effect sizes by comparing good and regular listening, which suggests that Listening Circles improve listening, a finding that can be used for research purposes and field applications.

This study also sheds light on a mechanism that might succeed where feedback interventions fail. Feedback interventions include, among other things, telling employees something about their wrongdoings with the often false hope that it will improve their performance, but has been found to have destructive effects (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). On the contrary, our findings demonstrate that merely listening makes employees simultaneously aware of both positive and negative aspects of an attitude. They thus hint that managers who listen to their employees might make these employees aware of their mistakes without having to say anything about it. This awareness, originating from the employee, and not from the manager, might be more effective in changing behaviour. This argument is supported by the notion that persuasion is more effective and stable when it comes from within (self-persuasion) the person than when it comes from an external source (Aronson, 1999)

The difference between learning from the Listening Circle and learning from feedback is akin to the difference between the Theory of Experiential Learning (Kolb, 1984) and didactic learning. The Theory of Experiential Learning argues that learning is more efficient when carried out through experience (Kolb, 1984; Kolb, Boyatzis, & Mainemelis, 2001) than when carried out though rote learning, where the learner plays a relatively passive role. For example, a manager probably will not get an employee to become a better listener by giving the following feedback: “You should pay more attention to the needs our customers”, or “you should read this self-help book on how to become a better listener”. On the contrary, if the manager provides the employee with an opportunity for experiential learning, by sending the employee to a Listening Circle workshop, the employee will understand from within the need to acquire better listening skills and will have the opportunity to practise it, thus increasing the chances for the desired outcome.

The reduction in social anxiety may indicate that the Listening Circle is useful in enhancing employees’ subjective well-being. It is congruent with previous work that found that discussing problems with other employees (i.e., social support) is negatively associated with negative affect and positively associated with problem-solving abilities (Daniels, Beesley, Wimalasiri, & Cheyne, 2013). Because one of the outcomes of the Listening Circle is that employees were better able to acknowledge and tolerate contradictions, they may also be able to solve problems in a more efficient manner, which also requires “seeing the big picture”.

The results might also suggest that the Listening Circle can be implemented as an effective continuing professional development (CPD) programme for employees aimed at enhancing individual well-being skills. Currently, the vast majority of CPD programmes in organizations are aimed at enhancing job performance (for a review, see Collin, Van der Heijden, & Lewis, 2012). Continued implementation of the Listening Circle in the workplace may increase job performance by training employees to enhance their well-being skills.

Limitations and future research

These studies have several limitations that require comment. First, the design was quasi-experimental. However, the claim for causality is bolstered by the fact that the findings were in the direction of those found in controlled laboratory experiments. Second, there may have been a demand effect with regard to reported listening in the Listening Circle workshop. However, this argument does not explain the effect on the other DVs (social anxiety, reflective self-awareness, objective-attitude ambivalence and attitude extremity). Nevertheless, the reciprocal act of talking and listening in the Listening Circle could have reduced social anxiety, this is because an attendee could have taken the perspective of an active listener more easily after being an active speaker, because participants always spoke and listened.

These studies were not designed to explore the organizational outcomes of the listening-induced attitude change. Experiencing objective ambivalence without subjective ambivalence was found to generate many beneficial outcomes for employees (Rothman, Pratt, Rees, & Vogus, 2016). These include motivation to engage in balanced consideration of multiple perspectives (Rees, Rothman, Lehavy, & Sanchez- Burks, 2013), the broadening of employees’ attention span (Fong & Tiedens, 2002), emotional and physical flexibility (Larsen, Hemenover, Norris, & Cacioppo, 2003) and trust in relationships (Pratt & Dirks, 2007). Hence, future studies should test whether participation in a Listening Circle transfers to the workplace and affects these work-related outcomes.

Finally, reports on Listening Circles indicate that multiple Listening Circle sessions may be beneficial (Garrett & EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF WORK AND ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY 673 Crutchfield, 1997; Waldemar et al., 2016). Thus, future research should assess what dosage of participation in Listening Circles can lead to stable changes. In all likelihood, the Listening Circle will contribute to positive and enduring organizational outcomes if it becomes part of the organizational routine, such as weekly meetings held as a Listening Circle (for the need to create organizational architecture that supports listening organizationally, see Macnamara, 2015). Regardless of these limitations, our corroboration of Rogers’ ideas in the workplace suggests that listening of the type that induced by Listening Circle can contribute to humanization, willingness to change and reduced extremity in the workplace.

Conclusion

The Listening Circle paradigm was found to be an effective intervention in improving employees’ listening abilities, making them less socially anxious and changing their attitudes. This is one of the first works to test Rogers’ core theoretical argument (Rogers, 1980) concerning the positive processes induced by listening in an organizational context. We hope that this work will shed light on the importance of using the Listening Circle as a method for increasing the quality of relationships in the workplace and will pave the way for more research about listening in organizations.

Notes

(*1) For example, http://www.heart-source.com/council/way_of_coun cil_page.html.

(*2) The purpose of this instruction is to take pressure off the attendees. The vast majority of the participants choose to actively participate.

(*3) Most employees who participated in the workshops were not previously acquainted with each other.

(*4) In case other employees might know who that person was.

(*5) One of the Listening Circle’s instructors provided to us with this information. The researchers were not present in the room at the time of the workshops.

(*6) In all studies we obtained similar results when we analysed the data by computing a residual score for each variable and submitted it to an independent t-test.

(*7) In all studies we obtained similar results when using the manipulation check (listening perception) as the independent variable, instead of the workshop type.

(*8) At the high-tech company attendees in both groups conversed at the exact same times (10:30 and 13:00). The Listening Circle in the school took place on a different day from 9:15 to 11:00. Note that the Listening Circles in this study were shorter than the Listening Circles in Study 1 and Study 2.

(*9) There was no difference for any of the variables between attendees in the Listening Circle at the high-tech company and the Listening Circle at the school.

(*10) Note that our focal hypothesis regarding subjective ambivalence referred to the buffering role of listening on the association between objective and subjective ambivalence, which was supported in Study 2 and Study 3. The main effect of listening on subjective ambivalence was similar in magnitude to the effect obtained in laboratory experiments (Itzchakov et al., 2017), where the metaanalytic effect was significant on a large sample size (N = 632).

(*11) Note that this research expands Itzchakov et al. (2017), by including reflective self-awareness in the model.

(*12) Subjective ambivalence was measured in two studies, N = 149.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eran Halevy and Nurit Halevy-El-Yosef for allowing us to collect data in their Listening Circles and for facilitating our access to collect data in other workshops and Dov Eden for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the Recanati Fund at the School of Business Administration and by The Israel Science Foundation (145/12) to the second author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Recanati Fund at the School of Business Administration and by The Israel Science Foundation (145/12) to the second author.

References

- Aakre, J. M., Lucksted, A., & Browning-McNee, L. A. (2016). Evaluation of youth mental health first aid USA: A program to assist young people in psychological distress. Psychological services, 13, 121. doi:10.1037/ser0000063

- Ames, D., Maissen, L. B., & Brockner, J. (2012). The role of listening in interpersonal influence. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 345–349. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.010

- Aronson, E. (1999). The power of self-persuasion. American Psychologist, 54, 875. doi:10.1037/h0088188

- Ashforth, B. E., Rogers, K. M., Pratt, M. G., & Pradies, C. (2014). Ambivalence in organizations: A multilevel approach. Organization Science, 25, 1453– 1478. doi:10.1287/orsc.2014.0909

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 941–952. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.941

- Bergeron, J., & Laroche, M. (2009). The effects of perceived salesperson listening effectiveness in the financial industry. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 14, 6–25. doi:10.1057/fsm.2009.1

- Berson, Y., & Avolio, B. J. (2004). Transformational leadership and the dissemination of organizational goals: A case study of a telecommunication firm. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 625–646. doi:10.1016/j. leaqua.2004.07.003

- Bodie, G., Jones, S. M., Vickery, A. J., Hatcher, L., & Cannava, K. (2014). Examining the construct validity of enacted support: A multitrait–multimethod analysis of three perspectives for judging immediacy and listening behaviors. Communication Monographs, 81, 495–523. doi:10.1080/03637751.2014.957223

- Bommelje, R. (2012). The listening circle: Using the SBI model to enhance peer feedback. International Journal of Listening, 26, 67–70. doi:10.1080/ 10904018.2012.677667

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Brehm, J. W. (1972). Responses to loss of freedom: A theory of psychological reactance. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

- Brink, K. E., & Costigan, R. D. (2014). Oral communication skills: Are the priorities of the workplace and AACSB-accredited business programs aligned? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14, 205–221. doi:10.5465/amle.2013.0044

- Briñol, P., Petty, R. E., Gallardo, I., & DeMarree, K. G. (2007). The effect of self-affirmation in nonthreatening persuasion domains: Timing affects the process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1533–1546. doi:10.1177/0146167207306282

- Brownell, J. (1990). Perceptions of effective listeners: A management study. Journal of Business Communication, 27, 401–415. doi:10.1177/ 002194369002700405

- Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. (2012). The power of being heard: The benefits of ‘perspective-giving’ in the context of intergroup conflict. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 855–866. doi:10.1016/j. jesp.2012.02.017

- Canlas, J. M., Miller, R. B., Busby, D. M., & Carroll, J. S. (2015). Same-race and interracial Asian-white couples: Relational and social contexts and relationship outcomes. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 46, 307–328.

- Castro, D. R., Kluger, A. N., & Itzchakov, G. (2016). Does avoidance-attachment style attenuates the benefits of being listened to? European Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 762–775. doi:10.1002/ejsp.v46.6

- Collin, K., Van der Heijden, B., & Lewis, P. (2012). Continuing professional development. International journal of training and development, 16, 155–163. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2419.2012.00410.x

- Daniels, K., Beesley, N., Wimalasiri, V., & Cheyne, A. (2013). Problem solving and well-being: Exploring the instrumental role of job control and social support. Journal of Management, 39, 1016–1043. doi:10.1177/ 0149206311430262

- Davidson, J. A., & Versluys, M. (1999). Effects of brief training in cooperation and problem solving on success in conflict resolution. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 5, 137. doi:10.1207/ s15327949pac0502_3

- De Lucio, L. G., López, F. J. G., López, M. T. M., Hesse, B. M., & Vaz, M. D. C. (2000). Training programme in techniques of self-control and communication skills to improve nurses’ relationships with relatives of seriously ill patients: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 425–431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01493.x

- DeMarree, K. G., Wheeler, S. C., Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2014). Wanting other attitudes: Actual–desired attitude discrepancies predict feelings of ambivalence and ambivalence consequences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 5–18. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2014.02.001

- Drollinger, T., & Comer, L. B. (2013). Salesperson’s listening ability as an antecedent to relationship selling. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 28, 50–59. doi:10.1108/08858621311285714

- Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. (2003). The power of high quality connections. In K. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 263–278). San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative science quarterly, 44, 350–383. doi:10.2307/2666999

- Fabrigar, L. R., MacDonald, T. K., & Wegener, D. T. (2005). The structure of attitudes. In D. Albarracı´n, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 79–124). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

- Field, A. P., & Gillett, R. (2010). How to do a meta-analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 63, 665–694. doi:10.1348/000711010X502733

- Fong, C. T., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2002). Dueling experiences and dual ambivalences: Emotional and motivational ambivalence ofwomen in high status positions. Motivation and Emotion, 26, 105–121. doi:10.1023/A:1015198209285

- Frei, J. R., & Shaver, P. R. (2002). Respect in close relationships: Prototype definition, self-report assessment, and initial correlates. Personal Relationships, 9, 121–139. doi:10.1111/pere.2002.9.issue-2

- Garrett, M. T., & Crutchfield, L. B. (1997). Moving full circle: A unity model of group work with children. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 22, 175–188. doi:10.1080/01933929708414379

- Goh, J. X., Hall, J. A., & Rosenthal, R. (2016). Mini meta-analysis of your own studies: Some arguments on why and a primer on how. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10, 535–549. doi:10.1111/spc3.v10.10

- Google. (2017). Retrieved March 4, 2017, from https://rework.withgoogle. com/guides/managers-set-and-communicate-a-team-vision/steps/lis ten-and-reflect/

- Graybill, D. (1986). A multiple-outcome evaluation of training parents in active listening. Psychological Reports, 59, 1171–1185. doi:10.2466/pr0.1986.59.3.1171

- Heider, F. (1946). Attitudes and cognitive organization. The Journal of psychology, 21, 107–112. doi:10.1080/00223980.1946.9917275

- Heller, J. F., Pallak, M. S., & Picek, J. M. (1973). The interactive effects of intent and threat on boomerang attitude change. Journal of personality and social psychology, 26, 273. doi:10.1037/h0034461

- Itzchakov, G., Castro, D. R., & Kluger, A. N. (2016). If you want people to listen to you, tell a story. International Journal of Listening, 30, 120–133. doi:10.1080/10904018.2015.1037445

- Itzchakov, G., Kluger, A. N., & Castro, D. R. (2017). I am aware of my inconsistencies but can tolerate them: The effect of high quality listening on speakers’ attitude ambivalence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 105–120. doi:10.1177/0146167216675339

- Johnson, I. W., Pearce, C. G., Tuten, T. L., & Sinclair, L. (2003). Self-imposed silence and perceived listening effectiveness. Business Communication Quarterly, 66, 23–38. doi:10.1177/108056990306600203

- Johnston, M. K., Reed, K., & Lawrence, K. (2011). Team Listening Environment (TLE) scale development and validation. Journal of Business Communication, 48, 3–26. doi:10.1177/0021943610385655

- Jones, S. M., Bodie, G. D., & Hughes, S. D. (2016). The impact of mindfulness on empathy, active listening, and perceived provisions of emotional support. Communication Research. doi:10.1177/0093650215626983

- Kaplan, K. J. (1972). On the ambivalence-indifference problem in attitude theory and measurement: A suggested modification of the semantic differential technique. Psychological Bulletin, 77, 361. doi:10.1037/h0032590

- Kashdan, T. B., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Expanding the topography of social anxiety an experience-sampling assessment of positive emotions, positive events, and emotion suppression. Psychological Science, 17, 120– 128. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01674.x

- Katz, L. F., & Woodin, E. M. (2002). Hostility, hostile detachment, and conflict engagement in marriages: Effects on child and family functioning. Child Development, 73, 636–651. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00428

- Kennedy, D. (2014). Neoteny, dialogic education and an emergent psychoculture: Notes on theory and practice. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 48, 100–117. doi:10.1111/jope.2014.48.issue-1

- Kluger, A. N., & Bouskila-Yam, O. (in press). Facilitating listening scale: (Bouskila-Yam & Kluger, 2011, December). In D. L. Worthington & G. D. Bodie (Eds.), The sourcebook of listening research: Methodology and measures. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 254–284. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254

- Kluger, A. N., & Zaidel, K. (2013). Are listeners perceived as leaders? International Journal of Listening, 27, 73–84. doi:10.1080/10904018.2013.754283

- Knowles, E. S., & Linn, J. A. (2004). Resistance and persuasion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2001). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, 1, 227–247.

- Krosnick, J. A., Boninger, D. S., Chuang, Y. C., Berent, M. K., & Carnot, C. G. (1993). Attitude strength: One construct or many related constructs? Journal of personality and social psychology, 65, 1132. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1132

- Krosnick, J. A., & Petty, R. E. (1995). Attitude strength: An overview. Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences, 4, 1–24.

- Larsen, J. T., Hemenover, S. H., Norris, C. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Turning adversity to advantage: On the virtues of the coactivation of positive and negative emotions. In L. G. Aspinwall & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.) A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology (pp. 211–225).

- Lawrence, W., Black, C., Tinati, T., Cradock, S., Begum, R., Jarman, M., . . . Barker, M. (2016). ‘Making every contact count’: Evaluation of the impact of an intervention to train health and social care practitioners in skills to support health behaviour change. Journal of health psychology, 21, 138–151. doi:10.1177/1359105314523304

- Lee, F. L., & Chan, J. M. (2009). The political consequences of ambivalence: The case of democratic reform in Hong Kong. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 21, 47–64. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edn053

- Levinson, W., Roter, D. L., Mullooly, J. P., Dull, V. T., & Frankel, R. M. (1997). Physician-patient communication – The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA-Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 553–559. doi:10.1001/jama.277.7.553

- Liberman, A., & Chaiken, S. (1992). Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 669–679. doi:10.1177/0146167292186002

- Lloyd, K. J., Boer, D., Keller, J. W., & Voelpel, S. (2014). Is my boss really listening to me? The impact of perceived supervisor listening on emotional exhaustion, turnover intention, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2242-4

- Lloyd, K. J., Boer, D., Kluger, A. N., & Voelpel, S. C. (2015). Building trust and feeling well: Examining intraindividual and interpersonal outcomes and underlying mechanisms of listening. International Journal of Listening, 29, 12–29. doi:10.1080/10904018.2014.928211

- Lobdell, C. L., Sonoda, K. T., & Arnold, W. E. (1993). The influence of perceived supervisor listening behavior on employee commitment. The Journal of The International Listening Association, 7, 92–110. doi:10.1080/10904018.1993.10499116

- Macnamara, J. (2015). The work and ‘architecture of listening’: Requisites for ethical organisation-public communication. Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics, 12, 29–37.

- Maio, G. R., Bell, D. W., & Esses, V. M. (1996). Ambivalence and persuasion: The processing of messages about immigrant groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32, 513–536. doi:10.1006/jesp.1996.0023

- Maio, G. R., & Haddock, G. (2010). The psychology of attitudes and attitude change. London: Sage.

- McNaughton, D., Hamlin, D., McCarthy, J., Head-Reeves, D., & Schreiner, M. (2008). Learning to listen: Teaching an active listening strategy to preservice education professionals. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 27, 223–231. doi:10.1177/0271121407311241

- Miller, J., & Stiver, I. (1997). The healing connection: How women form relationships in therapy and in life. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Morris, S. B., & DeShon, R. P. (2002). Combining effect size estimates in metaanalysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7, 105–125. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.105

- Pasupathi, M., & Hoyt, T. (2010). Silence and the shaping of memory: How distracted listeners affect speakers’ subsequent recall of a computer game experience. Memory, 18, 159–169. doi:10.1080/09658210902992917

- Pasupathi, M., & Rich, B. (2005). Inattentive listening undermines selfverification in personal storytelling. Journal of Personality, 73, 1051– 1085. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00338.x

- Pines, M. A., Ben-Ari, A., Utasi, A., & Larson, D. (2002). A cross-cultural investigation of social support and burnout. European Psychologist, 7, 256–264. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.7.4.256

- Pratt, M. G., & Barnett, C. K. (1997). Emotions and unlearning in Amway recruiting techniques: Promoting change through ‘safe’ ambivalence. Management Learning, 28, 65–88. doi:10.1177/1350507697281005

- Pratt, M. G., & Dirks, K. (2007). Rebuilding trust and restoring positive relationships: A commitment based view of trust. In J. Dutton & B. Baggins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work: Building: A theoretical and research foundation (pp. 117–158). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.