- Sections

- Figures

- Tables

- References

- The merits of group-based listening training programs

- The importance of listening training for teachers

- Listening and Autonomy need satisfaction

- Listening and Psychological safety

- Listening and Relational energy

- The present research

- Method

- Results

- General discussion

- Conclusion

- References

7.1. Participants

7.1.1. Procedure

7.1.1.1 Listening training

7.2. Measures

7.2.1. Listening perception

7.2.2. Psychological safety

7.2.3. Autonomy need satisfaction

7.2.4. Relational energy

8.1. Growth models

8.1.1. Listening perception

8.1.2. Psychological safety

8.1.3. Autonomy need satisfaction

8.1.4. Relational energy

8.2. Structural models

9.1. Limitations and future research

- Alzamil, J. (2021). Listening skills: Important but difficult to learn. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 12, 366–374.

- Baker, W. E. (2019). Emotional energy, relational energy, and organizational energy: Toward a multilevel model. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 373–395.

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 941–952.

- Bensing, J. M., & Sluijs, E. M. (1985). Evaluation of an interview training course for general practitioners. Social science & medicine (1982), 20, 737–744.

- Bodie, G., Fitch-Hauser, M., & Powers, W. (2011). Teaching Social Skills. In Instructional Design: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools and Applications (pp. 1689–1713). IGI Global.

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods. Guilford.

- Boyatzis, R., Smith, M. L., & Van Oosten, E. (2019). Helping people change: Coaching with compassion for lifelong learning and growth. Harvard Business Press.

- Boyatzis, R. E., & Rochford, K. (2020). Relational climate in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00085

- Castro, D. R., Anseel, F., Kluger, A. N., Lloyd, K. J., & Turjeman-Levi, Y. (2018). Mere listening effect on creativity and the mediating role of psychological safety. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 12, 489–502.

- Castro, D. R., Kluger, A. N., & Itzchakov, G. (2016). Does avoidance-attachment style attenuate the benefits of being listened to? European Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 762–775.

- Čepić, R., Vorkapić, S. T., & Šimunić, Z. (2018). Autonomy and readiness for professional development: How do preschool teachers perceive them? In L. G. Chova, A. López Martinez, & I. Candel Torres (Eds.), EDULEARN18 Proceedings (pp. 1319–1327). Palma de Mallorca, Spain: IATED Academy.

- Cojuharenco, I., & Karelaia, N. (2020). When leaders ask questions: Can humility premiums buffer the effects of competence penalties? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 156, 113–134.

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers' psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000088

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. Available online from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Educating_Whole_Child_REPORT.pdf

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Sykes, G. (2003). Wanted, a national teacher supply policy for education: The right way to meet the “highly qualified teacher” challenge. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11, 33.

- De Lucio, L. G., Lopez, F. J. G., Lopez, M. T. M., Hesse, B. M., & Vaz, M. D. C. (2000). Training programme in techniques of self-control and communication skills to improve nurses' relationships with relatives of seriously ill patients: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 425–431.

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43.

- Dikilitaş, K., Griffiths, C., & Tajeddin, Z. (2020). Teacher autonomy and good language teachers. Lessons from good language teachers, 54–66.

- Doerr, H. M. (2006). Teachers' ways of listening and responding to students' emerging mathematical models. ZDM, 38, 255–268.

- Dynarski, M. (2008). Dropout Prevention IES PRACTICE GUIDE.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23–43.

- Edwards, N., Peterson, W. E., & Davies, B. L. (2006). Evaluation of a multiple component intervention to support the implementation of a ‘therapeutic relationships’ best practice guideline on nurses' communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling, 63, 3–11.

- Endrejat, P. C., Klonek, F. E., Müller-Frommeyer, L. C., & Kauffeld, S. (2021). Turning change resistance into readiness: How change agents' communication shapes recipient reactions. European Management Journal, 39, 595–604.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

- Fernandes, P. R. S., Jardim, J., & Lopes, M. C. S. (2021). The soft skills of special education teachers: Evidence from the literature. Education Sciences, 11, 125. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/11/3/125

- Gilbert, M. B. (1988). Listening in school: I know you can hear me—but are you listening? International Listening Association, 2, 121–132.

- Göksoy, S., & Argon, T. (2016). Conflicts at schools and their impact on teachers. Journal of Education and Training studies, 4, 197–205.

- Greenglass, E. R., Fiksenbaum, L., & Burke, R. J. (2020). The relationship between social support and burnout over time in teachers In Occupational Stress (pp. 239–248). CRC Press.

- Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20, 90–100.

- Hinz, J., Stephens, J. P., & Van Oosten, E. B. (2022). Toward a pedagogy of connection: A critical view of being relational in listening. Management Learning, 53, 76–97.

- Hughes, S., & Lewis, H. (2020). Tensions in current curriculum reform and the development of teachers' professional autonomy. The Curriculum Journal, 31, 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.25

- Hunter, E. M., & Wu, C. (2016). Give me a better break: Choosing workday break activities to maximize resource recovery. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000045

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 499–534. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038003499

- Itzchakov, G. (2020). Can listening training empower service employees? The mediating roles of anxiety and perspective-taking. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29, 938–952.

- Itzchakov, G., Castro, D. R., & Kluger, A. N. (2016). If you want people to listen to you, tell a story. International Journal of Listening, 30, 120–133.

- Itzchakov, G., & DeMarree, K. G. (2022). Attitudes in an interpersonal context: Psychological safety as a route to attitude change. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 4242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.932413

- Itzchakov, G., DeMarree, K. G., Kluger, A. N., & Turjeman-Levi, Y. (2018). The listener sets the tone: High-quality listening increases attitude clarity and behavior-intention consequences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44, 762–778.

- Itzchakov, G., & Grau, J. (2022). High-quality listening in the age of COVID-19. Organizational Dynamics, 51, 100820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100820

- Itzchakov, G., & Kluger, A. N. (2017a). Can holding a stick improve listening at work? The effect of listening circles on employees' emotions and cognitions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26, 663–676.

- Itzchakov, G., & Kluger, A. N. (2017b). The listening circle: A simple tool to enhance listening and reduce extremism among employees. Organizational Dynamics, 46, 220–226.

- Itzchakov, G., & Weinstein, N. (2021). High-quality listening supports speakers' autonomy and self-esteem when discussing prejudice. Human Communication Research, 47, 248–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab003

- Itzchakov, G., Weinstein, N., & Cheshin, A. (2022). Learning to listen: Downstream effects of listening training on employees' relatedness, burnout, and turnover intentions. Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22103

- Itzchakov, G., Weinstein, N., Legate, N., & Amar, M. (2020). Can high quality listening predict lower speakers' prejudiced attitudes? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 91, 104022.

- Itzchakov, G., Reis, H. T., & Weinstein, N. (2021). How to foster perceived partner responsiveness: High-quality listening is key. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12648

- Itzchakov, G., Weinstein, N., Saluk, D., & Amar, M. (2022). Connection heals wounds: Feeling listened to reduces speakers' loneliness following a social rejection disclosure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 01461672221100369. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221100369

- Johnston, M. K., Reed, K., & Lawrence, K. (2011). Team listening environment (TLE) scale: Development and validation. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 48, 3–26.

- Joussemet, M., Mageau, G. A., & Koestner, R. (2014). Promoting optimal parenting and children's mental health: A preliminary evaluation of the how-to parenting program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 949–964.

- Kadel, P. B. (2021). Challenges of teacher autonomy for professional competence. Interdisciplinary Research in Education, 5, 39–46.

- Kennedy, D. M., Nordrum, J. T., Edwards, F. D., Caselli, R. J., & Berry, L. L. (2015). Improving service quality in primary care. American Journal of Medical Quality, 30, 45–51.

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Kluger, A. N., & Itzchakov, G. (2022). The power of listening at work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9, 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-091013

- Kluger, A. N., Malloy, T. E., Pery, S., Itzchakov, G., Castro, D. R., Lipetz, L., Sela, Y., Turjeman-Levi, Y., Lehmann, M., New, M., & Borut, L. (2021). Dyadic listening in teams: Social relations model. Applied Psychology, 70, 1045–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12263

- Kubota, S., Mishima, N., & Nagata, S. (2004). A study of the effects of active listening on listening attitudes of middle managers. Journal of Occupational Health, 46, 60–67.

- Kun, A., & Gadanecz, P. (2022). Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian teachers. Current Psychology, 41, 185–199.

- La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 367–384.

- Li, C., Dong, Y., Wu, C.-H., Brown, M. E., & Sun, L.-Y. (2022). Appreciation that inspires: The impact of leader trait gratitude on team innovation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(4), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2577

- Lloyd, K. J., Boer, D., Keller, J. W., & Voelpel, S. (2015). Is my boss really listening to me? The impact of perceived supervisor listening on emotional exhaustion, turnover intention, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 509–524.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want. penguin.

- Maas, C. J., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology, 1, 86–92.

- Maitlis, S., & Christianson, M. (2014). Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Academy of Management Annals, 8, 57–125.

- Malloy, T. E., Kluger, A. N., Martin, J., & Pery, S. (2021). Women listening to women at zero-acquaintance: Interpersonal befriending at the individual and dyadic levels. International Journal of Listening, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2021.1884080

- McCallum, F. (2021). In Wellbeing and Resilience Education (pp. 183–208). Routledge. Teachers' wellbeing during times of change and disruption.

- McNaughton, D., Hamlin, D., McCarthy, J., Head-Reeves, D., & Schreiner, M. (2008). Learning to listen: Teaching an active listening strategy to preservice education professionals. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 27, 223–231.

- Mineyama, S., Tsutsumi, A., Takao, S., Nishiuchi, K., & Kawakami, N. (2007). Supervisors' attitudes and skills for active listening with regard to working conditions and psychological stress reactions among subordinate workers. Journal of Occupational Health, 49, 81–87.

- Neill, M. S., & Bowen, S. A. (2021). Employee perceptions of ethical listening in US organizations. Public Relations Review, 47, 102123.

- O'Brien, N., O'Brien, W., Costa, J., & Adamakis, M. (2022). Physical education student teachers' wellbeing during Covid-19: Resilience resources and challenges from school placement. European Physical Education Review, 28(4), 873–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X221088399

- Owens, B. P., Baker, W. E., Sumpter, D. M., & Cameron, K. S. (2016). Relational energy at work: Implications for job engagement and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000032

- Owens, B. P., & Hekman, D. R. (2016). How does leader humility influence team performance? Exploring the mechanisms of contagion and collective promotion focus. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 1088–1111.

- Pasupathi, M., & Billitteri, J. (2015). Being and becoming through being heard: Listener effects on stories and selves. International Journal of Listening, 29, 67–84.

- Pasupathi, M., & Rich, B. (2005). Inattentive listening undermines self-verification in personal storytelling. Journal of Personality, 73, 1051–1086.

- Pellerone, M. (2021). Self-perceived instructional competence, self-efficacy and burnout during the covid-19 pandemic: A study of a group of Italian school teachers. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11, 496–512.

- Pines, A. M., Ben-Ari, A., Utasi, A., & Larson, D. (2002). A cross-cultural investigation of social support and burnout. European Psychologist, 7, 256–264.

- Pontefract, D. (2019). The Wasted Dollars of Corporate Training Programs. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/danpontefract/2019/09/15/the-wasted-dollars-of-corporate-training-programs/?sh=18f7ae7471f9

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage., 1.

- Rautalinko, E., & Lisper, H.-O. (2003). Effects of training reflective listening in a corporate setting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 281–299.

- Rave, R., Itzchakov, G., Weinstein, N., & Reis, H. T. (2022). How to get through hard times: Principals' listening buffers teachers' stress on turnover intention and promotes organizational citizenship behavior. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03529-6

- Robertson, J. (2009). Coaching leadership learning through partnership. School Leadership & Management, 29, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430802646388

- Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin.

- Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50, 4–36. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831212463813

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

- Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S. I., Kraiger, K., & Smith-Jentsch, K. A. (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13, 74–101.

- Sarros, J. C., & Sarros, A. M. (1992). Social support and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Administration, 30, 09578239210008826. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578239210008826

- Schultz, K., Jones-Walker, C. E., & Chikkatur, A. P. (2008). Listening to students, negotiating beliefs: Preparing teachers for urban classrooms. Curriculum Inquiry, 38, 155–187.

- Shahid, S., & Din, M. (2021). Fostering psychological safety in teachers: The role of school leadership, team effectiveness & organizational culture. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management, 9, 122–149.

- Sheridan, S., Williams, P., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2014). Group size and organisational conditions for children's learning in preschool: A teacher perspective. Educational Research, 56, 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2014.965562

- Sun, Y., & Huang, J. (2019). Psychological capital and innovative behavior: Mediating effect of psychological safety. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 47, 1–7.

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D'Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of educational research, 83, 357–385. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483907

- Tynan, R. (2005). The effects of threat sensitivity and face giving on dyadic psychological safety and upward communication 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 223–247.

- Van Hasselt, V. B., Baker, M. T., Romano, S. J., Schlessinger, K. M., Zucker, M., Dragone, R., & Perera, A. L. (2006). Crisis (hostage) negotiation training: A preliminary evaluation of program efficacy. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33, 56–69.

- Van Quaquebeke, N., & Felps, W. (2018). Respectful inquiry: A motivational account of leading through asking questions and listening. Academy of Management Review, 43, 5–27.

- Weiner, J., Francois, C., Stone-Johnson, C., & Childs, J. (2021). Keep safe, keep learning: Principals' role in creating psychological safety and organizational learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Education, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.618483

- Weinstein, N., Huo, A., & Itzchakov, G. (2021). Parental listening when adolescents self-disclose: A preregistered experimental study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 209, 105178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105178

- Weinstein, N., Itzchakov, G., & Legate, N. (2022). The motivational value of listening during intimate and difficult conversations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16, e12651. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12651

- Weinstein, N., Legate, N., Ryan, W. S., Sedikides, C., & Cozzolino, P. J. (2017). Autonomy support for conflictual and stigmatized identities: Effects on ownership and psychological health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64, 584–599.

- K. R. Wentzel, & G. B. Ramani, (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of social influences in school contexts: Social-emotional, motivation, and cognitive outcomes. Routledge.

- Worth, J., & Van den Brande, J. (2020). Teacher autonomy: How does it relate to job satisfaction and retention? National Foundation for Educational Research. Available from https://www.nfer.ac.uk/teacher-autonomy-how-does-it-relate-to-job-satisfaction-andretention/

- Yip, J., & Fisher, C. M. (2022). Listening in organizations: A synthesis and future agenda. Academy of Management Annals, 16, 657–679. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2020.0367

- Zimmerman, J. M., & Coyle, V. (2009). The way of council. Bramble Books.

Communicating For Workplace Connection:

A longitudinal study of the outcomes of listening training

on teachers’ autonomy, psychological safety, and relational climate

Communicating For Workplace Connection: A longitudinal study of the outcomes of listening training on teachers’ autonomy, psychological safety, and relational climate

- Department of Human Services, The University of Haifa, Abba Khoushy Ave 199, Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel.

- School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, University of Reading, Reading, UK.

- Department of Social‐Community Education, Gordon Academic College of Education, Haifa, Israel.

* Corresponding author

Received: 1 August 2022 / Revised: 5 October 2022 / Accepted: 18 November 2022 / Published: 13 December 2022

Abstract

Training teachers to listen may enable them to experience increasingly attentive and open peer relationships at work. In the present research, we examined the outcomes of a year-long listening training on school teachers' listening abilities and its downstream consequences on their relational climate, autonomy, and psychological safety. Teachers in two elementary schools engaged in a similar listening training program throughout the entire school year. The measures included indicators of a supportive relational climate that are known to be important to teacher well-being, namely, autonomy, psychological safety, and relational energy. Results of growth curve modeling showed linear increases in all three outcomes, such that more listening training corresponded to a more positive relational climate. Specifically, the teachers reported increasingly higher quality listening from their group-member teachers, felt more autonomy-satisfied, psychologically safe, and relationally energetic. Furthermore, latent growth curve modeling indicated that the teachers' listening perception was positively and significantly associated with all three outcomes. We concluded that listening training is associated with teachers perceiving higher quality listening from their peers and, therefore, feeling more autonomy satisfied, psychologically safe, and relationally energetic and discuss theoretical and practical implications.

Practitioner points

- Training teachers to listen in a group setting helps them feel safe to express themselves openly with others at work.

- Listening training for teachers is essential for creating a sense of social connection with colleagues.

- Listening training for teachers achieved more benefits as teachers attended multiple training sessions.

KEYWORDS: autonomy, interpersonal listening, psychological safety, relational energy, training.

Teachers engage in a range of daily activities requiring cognitive and intellectual abilities and “softer” social and emotional skills that allow them to develop their professional praxis and students' academic engagement and learning. Therefore, these softer skills are closely linked to job performance in the education workplace (Fernandes et al., 2021). For this reason, educational research has been growing interest in promoting noncognitive skills, albeit mainly among students, such as social and emotional learning (Wentzel & Ramani, 2016).

Theoretical approaches to soft skills in the workplace suggest that teachers' ability to develop positive relationships depends largely on their capacity to listen well (Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022; Yip & Fisher, 2022). However, becoming a good listener requires extensive training (Itzchakov & Grau, 2020; Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022), as shown in studies on training programs in workplace environments (Itzchakov, 2020; Itzchakov et al., 2022; Rautalinko & Lisper, 2004). Despite its importance, there is little work on training teachers to listen. This shortcoming is important to address because teachers can thrive and flourish in a socially supportive work environment. Moreover, promoting a supportive work environment should help teachers deal with difficult times, which are prevalent in the teaching profession.

The longitudinal field study described here followed teachers who took part in a group-based listening training program to assess its benefits for the teachers themselves. Three outcomes were analyzed: psychological safety- the experience of taking risks in a safe interpersonal environment, autonomy need satisfaction- the feeling that one can engage in open and self-congruent expressions and actions, and relational energy- the sense of being vitalized from supportive interpersonal interactions.

1. The merits of group-based listening training programs

Group-based listening training programs have been implemented in several organizational settings with some success in terms of improved listening (Edwards et al., 2006; Itzchakov, 2020) and increased workplace well-being in the form of reduced burnout and turnover intentions (Itzchakov et al., 2022). One important reason why trainees benefit from this experience may be that groups create attentive and supportive climates where the participants feel able to listen efficaciously to others and simultaneously feel listened to by their colleagues (Itzchakov & Kluger, 2017b).

Despite growing evidence that listening training can benefit employees and the organization, to the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the downstream outcomes of listening training for teachers. Beyond the importance of teachers' ability to listen well to their students for their students' relational, emotional, and learning outcomes (Doerr, 2006; Schultz et al., 2008), listening training can also create closer and more open relationships among teachers when they feel that they are listened to by their peers. As such, good listening can be a powerful tool for supporting teachers' own well-being (Sarros & Sarros, 1992).

Studies have shown that when teachers feel stress, this negatively affects the quality of their work (Herman et al., 2018). However, recent literature suggests that the harmful outcomes of teaching-related stressors can be buffered when teachers feel listened to (Rave et al., 2022). Other work indicated that teachers who have positive relational experiences in their workplace that are shaped by the nature of their interactions with their peers show higher workplace well-being along with the three other key dimensions of positive relationships: autonomy, psychological safety, and energy deriving from a sense of relatedness with others (Kun & Gadanecz, 2022). The links between listening perception and each of these three constructs are discussed below.

2. The importance of listening training for teachers

To our knowledge, there is no documented research on training focusing on interpersonal listening for teachers. This gap is glaring because listening is one of the core skills that teachers need in schools (Gilbert, 1988) and is difficult to acquire (Alzamil, 2021). Moreover, teaching teachers to listen is a recommended first step to improving students' experience in the classroom. Specifically, to optimally promote skills among students, it is necessary to first promote teachers' listening skills through an intensive process that allows teachers to reflect on the practices being taught (see Darling-Hammond & Sykes, 2003).

Learning to listen makes teachers better educators. For example, McNaughton et al. (2008) found that preservice education professionals' listening training received positive evaluations from parents of preschool and school-age children. Listening training also improved teachers' interpersonal relationships at work (Bodie et al., 2011; Robertson, 2009). Positive work relationships are quite important in light of the movement within schools toward teacher collaboration and improving school climate (Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, 2018) and the tensions between interpersonal challenges that are typical to the culture of teaching (Thapa et al., 2013). Hence, the present study takes a closer look at what happens when teachers are taught to improve their listening skills.

3. Listening and Autonomy need satisfaction

People experience autonomy need satisfaction when they feel that they can act in volitional and self-congruent ways that reflect their values, interests, and emotions (Ryan & Deci, 2017). A growing body of research suggests that autonomy satisfaction promotes a sense of well-being in and out of the workplace, including benefiting teachers in school settings (Collie et al., 2016). When teachers feel their autonomy needs are satisfied, they stay with schools longer and are more satisfied with their work (Kadel, 2020; Worth & Van den Brande, 2020). Autonomy-supported individuals also seek to continue their professional development (Čepić et al., 2018) and are more effective in their work (Dikilitaş et al., 2020). In the absence of autonomy need satisfaction, teachers report higher burnout, which has implications for long-term retention (Greenglass et al., 2020).

Recently, high-quality listening has been theorized to be a key interpersonal behavior that can convey autonomy support (Weinstein et al., 2022). This is because high-quality listening creates a relational climate that promotes autonomy need satisfaction: high-quality listeners convey their understanding of others' perspectives, support others' values and interests by promoting open self-expression, and allow others to guide conversations volitionally (Deci et al., 2017). In addition, listeners who exhibit high-quality listening ask open-ended questions that allow individuals to reflect on their values, thoughts, and emotions (Itzchakov et al., in press). Such questions provide speakers with the autonomy to make sense of the situation from their own perspective (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014) and send an implicit message of “you have control” (Van Quaquebeke & Felps, 2018). Training programs that teach people how to provide autonomy support for others often involve training to listen with undivided attention to enhance perspective-taking (Joussemet et al., 2014).

Recent studies have supported the expected association between perceived listening and autonomy need satisfaction. In empirical work, Weinstein et al. (2021) found that parents' listening when adolescent children disclose a difficult event could satisfy children's autonomy. An in-person experiment similarly found that listening (this time in stranger-dyads) promoted the speakers' autonomy need satisfaction. Similarly, in the context of a difficult conversation, Itzchakov and Weinstein (2021) found that speakers who expressed prejudiced attitudes felt more autonomy when their listeners exhibited high-quality listening behavior compared to moderate-and-poor listening behaviors. Endrejat et al. (2021) found that employees' active listening skills were positively correlated with autonomy-supportive communication. To expand this developing line of research, the current study examined whether a group-based listening training program would contribute to a greater sense of fulfillment of teachers' autonomy.

4. Listening and Psychological safety

High-quality listening is characterized by a nonjudgmental approach on the part of the listener towards the speaker, which reduces the speaker's felt threat and apprehension of evaluation. This process provides speakers with a safe atmosphere, gives them the sense of feeling accepted (Rogers, 1980), and creates an atmosphere that can increase psychological safety when speakers feel a sense of trust and respect from others. This, in turn, encourages a sense of openness, requests for help, and self-disclosures (Edmondson, 1999; Edmondson & Lei, 2014; Tynan, 2005).

Psychological safety is one most crucial issues that teachers face at work (Shahid & Din, 2021). When teachers experience psychological safety, they can innovate to maximize their effectiveness, cultivating more creative learning climates (Sun & Huang, 2019). Studies that have evaluated undue restrictions on teachers have led to recommendations to bolster support for their psychological safety (Hughes & Lewis, 2020). Nevertheless, it is clear that establishing a climate of psychological safety in schools is fraught with difficulties (Weiner et al., 2021). However, when listeners provide their undivided attention, speakers feel that their thoughts and perspectives are considered (Castro et al., 2018; Itzchakov et al., 2018, 2020). By contrast, when speakers feel that their listeners are not attentive towards them, they become concerned with the listeners' negative reactions and avoid disclosing their perspectives (Pasupathi & Rich, 2005; Weinstein et al., 2021).

The current study focused on psychological safety at the individual level (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). In so doing, it extends previous explorations of the associations between listening perception and psychological safety (Castro et al., 2016, 2018; Itzchakov & DeMarree, 2022; Itzchakov et al., 2016; Li et al., 2022). Despite the supporting evidence from laboratory experiments and field studies on the role of listening in facilitating psychological safety, it remains unclear whether listening training programs can promote psychological safety over time during actual workplace training.

5. Listening and Relational energy

Relational energy is defined as the emotional energy that is “generated or depleted by social interactions” (Baker, 2019; p. 381). This construct is less well-studied in the organizational sciences (Boyatzis & Rochford, 2020; Boyatzis et al., 2019). Relational energy is fostered when interpersonal interactions increase the capacity to do work because of high-quality interpersonal connections (Baker, 2019).

Relational energy derives from conversations among employees (Owens & Baker, Sumpter, et al., 2016). Hence, listening is likely to play a vital role in its facilitation. The known antecedents of relational energy include writing a gratitude journal (Lyubomirsky, 2008), timing, and activities during breaks at work (Hunter & Wu, 2016). Social support also fosters relational energy (Owens & Hekman, 2016). Like social support, listening entails constructive behaviors as perceived by speakers (Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022). However, these two constructs are not isomorphic since listening includes “in the moment” behaviors that convey attention, comprehension, and positive intention of speakers, whereas social support is a more general, abstract concept and does not require a conversation (For more on the differences between listening and types of social support see; Itzchakov et al., 2021; Weinstein et al., 2022).

Listening may thus be an unexplored antecedent of relational energy. Episodic Listening Theory (Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022) suggests that good listeners create a mutual feeling of togetherness. To illustrate, when Tammy perceives that Amanda is listening to her well, Tammy feels more connected to Amanda and is energized by her interactions with Amanda. On the other hand, poor listening is likely to undermine relational energy because it can result in unsupportive or toxic work relationships. Supporting this view, studies have shown that the perception of good listening at work is negatively associated with emotional exhaustion (Lloyd et al., 2015; Mineyama et al., 2007; Pines et al., 2002).

6. The present research

Although research on teachers' listening training is only at its beginning, the outcomes are likely to contribute to a more positive school environment. More generally, organizations spend a tremendous amount of money on training. In 2018 alone, corporations in the United States invested over 87 billion dollars in training and development programs (Pontefract, 2019), pointing to the need for more empirical research to assess its outcomes (Salas et al., 2012). Examining the impact of training on employees' listening skills is of particular interest because most employees do not feel satisfied with their organizations' listening efforts. This problem may be remedied by effective workplace training (Neil & Bowen, 2021). To probe the benefits of teacher listening training in the school setting, a longitudinal study of a listening training program and its outcomes was conducted simultaneously in two elementary schools in Israel.

The goals of the present study were threefold. The first goal was to examine whether training teachers to listen facilitates a better listening climate at school (i.e., do their colleagues perceive them as better listeners?). Previous work found that listening training at the workplace facilitated better listening in professions such as medicine (Bensing & Sluijs, 1985; Kennedy et al., 2015), nursing (De Lucio et al., 2000), and negotiation (Van Hasselt et al., 2006). Previous work also found that listening training for teachers was viewed positively by the pupils' parents (McNaughton et al., 2008). However, we are unaware of research examining the effect of listening training on the listening climate between teachers themselves. Second, we wanted to examine whether listening training is associated with a motivation that stems from interpersonal relationships (i.e., relational energy); The third goal was to examine whether listening training for teachers is associated with more openness and less self-presentational concerns (i.e., psychological safety and autonomy). The research hypotheses were:

Hypothesis 1a: The listening training program will be positively associated with growth in teachers' autonomy levels.

Hypothesis 1b: Growth in teachers' listening ability will be positively associated with growth in their autonomy.

Hypothesis 2a: A listening training program will be associated with teachers' psychological safety growth.

Hypothesis 2b: Growth in teachers' listening ability would be positively associated with greater felt psychological safety.

Hypothesis 3a: A listening training program would be associated with teachers' relational energy growth.

Hypothesis 3b: Growth in teachers' listening ability will be positively associated with more relational energy.

7. Method

7.1. Participants

The entire teaching staff of two elementary schools participated in the training study. One teacher who only completed the questionnaires twice was excluded. The final sample size consisted of 53 teachers (Mage = 42.38, SD = 9.65, 92.7% female). This sample size was above the minimum threshold (n = 50) needed for unbiased standard errors at Level 2 at the between-teacher level (Maas & Hox, 2005). In the sample, 28 teachers were from one school and 25 from the other. Exploratory analysis indicated no difference in growth patterns for the research variables between the schools.

7.1.1. Procedure

The listening training program took place in two schools in the northern district of Israel. All the permanent teachers participated in the program. The teachers completed questionnaires at six time points before, during, and after training. Specifically, the teachers received a link with the questionnaires (in Hebrew) of the research variables programmed in Qualtrics, which they could complete on their computers, smartphones, or tablets. The first questionnaire was administered 2 weeks before the beginning of the program, 1 week before the school year. Once the school term began, assessments took place approximately every 5 weeks. The study received ethical approval.

We chose this sampling procedure for two reasons. First, a sensitivity power analysis indicated that six measurements have a power of 80% to detect a small effect size, Cohen's f = .14 for a within-participants repeated-measure design (Faul et al., 2007). Second, the principals in the two schools agreed that up to six times waves across the school year would be acceptable to the teachers (who participated in the study voluntarily) and would not create a burden for them. The principals felt that 5 weeks would be long enough to show changes but short enough that intervening events would not introduce unobserved error. We chose to administer the questionnaires at fixed-time intervals (5 weeks) between the measurements to reduce the effect of variable autocorrelations resulting from measurements that span over different time intervals (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Because only one teacher was excluded from the analyses, no missing data technique was applied. No portions of the dataset have been previously published.

The teachers in both schools were sent the questionnaires simultaneously. The program was composed of 15 sessions 2 weeks apart, each lasting 2 h (for a total of 30 h of training). Two listening program instructors, credentialed by an institution of higher learning, delivered the sessions in each school. A seventh wave of the questionnaires was administered 1 month after the program. However, because only a small percentage of the sample responded at this time point, it was not included in the analysis. That said, exploratory analyses, including data from this measurement wave, did not change the findings.

This research received ethical approval from the lead author's institution. In the information sheet provided to participants, we noted that participation is voluntary, and no identifying information is requested. We ensured anonymity by not asking for any identifying information aside from basic demographics (age, gender, seniority). Consistent with our IRB and to reduce social desirability concerns, the information sheet also stated that the raw data would not be shared with any member of the schools' management and will be used only for research purposes. At the end of each set of questionnaires, the teachers completed a four-digit code known only to match the data for longitudinal analysis.

7.1.1.1. Listening training

Each session consisted of theoretical content, dyadic and group exercises, reflections about the listening process, and homework. Throughout the program, teachers learned what constitutes high-quality listening and how it promotes a mutual connection between individuals and groups. They also learned the reasons that good listening is difficult to achieve. The teachers engaged in many hours of experiential practice. The listening activities were delivered in dyads, triads, quartets, octets, tens, and plenums. This decision was made to generalize findings across groups of different sizes and explores its effectiveness in both dyads and groups (Malloy et al., 2021). Moreover, the quality of listening in a group might depend on the size of the group. This is especially important for teachers because working with a group of nine students might require more effort than working with a group of three (Sheridan et al., 2014).

After each exercise, teachers reflected on their experience as speakers and listeners by sharing to what extent they felt listened to when they spoke. How well did they listen? What forces prevented them from listening? The teachers also learned techniques such as the listening circle, a well-established method for enhancing listening skills (Itzchakov & Kluger, 2017a, 2017b). In this activity, the attendees sit in a circle. No objects (i.e., a table) are placed between them to facilitate intimacy. Each person in the listening circle is instructed to speak briefly about a particular topic relevant to the group, as determined by instructors. When one person speaks, the others in the group pay undivided attention and do not provide feedback. The circle continues until every attendee has had a chance to speak or after several rounds. The attendees' perspectives in the circle remain confidential to build an atmosphere of closeness and safety (Zimmerman & Coyle, 2009).

The teachers also studied and practiced the primary overt and covert elements of listening: repeating the speaker's message in their own words (paraphrasing), providing reflections, avoiding giving advice or feedback, asking promoting questions, maintaining eye contact, and using body posture that conveys openness and curiosity, developing a nonjudgmental approach, and the intention to benefit the speaker (Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022). The teachers practiced each component in dyads and groups. For example, the teachers sat in a circle when learning about paraphrasing, being nonjudgmental, and accepting the speaker's freedom to self-express. In part, these skills were developed by learning how to use efficient verbal and nonverbal behaviors called “backchanneling” (Bavelas et al., 2000; Pasupathi & Billitteri, 2015), which involves listening to a speaker's emotions behind the content, awareness of the speaker's nonverbal behavior such as body language and facial expressions, and verbal cues that convey emotions such as the speaker's tone and intonation.

Along with the instruction, the teachers held group discussions that focused on essential issues concerning the school, such as conflicts between them and challenges in dealing with pupils and parents. During the basic training and throughout these discussions, the teachers also studied and practiced asking good questions (Cojuharenco & Karelaia, 2020; Van Quaquebeke & Felps, 2018), such as open questions that convey understanding and help speakers delve deeper into their thoughts rather than providing a surface-level response, and how to use questions during disagreements. They also focused on avoiding the distractions that prevent them from achieving good communication. These include judgments of the speaker's content, responding to smartphones, and interrupting (for a review of the “enemies” of listening, see Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022). Each teacher summarized the message of the adjacent teacher and only then took a stance. After each session, the teachers were given homework that included practicing the listening skills they had learned in the session. The teachers shared their experience with the homework assignments at the beginning of each subsequent session.

The instructors were certified in the same method and worked collaboratively. The instructors also participated in a weekly 1-h “instructors' meeting” on the method. The goal of the meeting was to share experiences between instructors and refresh procedures. They also met with a senior instructor of the method once a week to ensure synchronization, face challenges together, offer solutions to situations that arose, and discuss the continuation of the training.

7.2. Measures

Items for each measure were anchored on a 9-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely disagree; 5 = moderately agree; 9 = completely agree).

7.2.1. Listening perception

Teachers' listening perception was measured by asking each teacher to rate their co-participants' listening quality on the 7-item listening environment scale (Johnston et al., 2011). Example items are: “the other group members genuinely want to hear my point of view” and “the other group members show me that they understand what I say.” This measure showed consistently high reliabilities across the six measurements, ranging from .89 < α < .97.

This study had a multilevel design (time-points nested within teachers), so an intra-class correlation (ICC) was computed for each construct. The ICC for listening perception was 0.63. In other words, 63% of the variance in listening perception originated from differences between teachers (Level 2), whereas 37% of the variance originated from differences within each teacher across the measurements.

7.2.2. Psychological safety

Psychological safety was assessed on the scale developed by Edmondson (1999). This measure is composed of seven statements. Example items include “Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues” and “It is difficult to ask members of this team for help (reverse scored),” .78 < α < .84, ICC = 0.52.

7.2.3. Autonomy need satisfaction

Five items from the Autonomy at Work Scale, a subscale of the Basic Need Satisfaction at Work measure (La Guardia et al., 2000), were used. Example items are: “I am free to express my ideas and opinions on the job” and “I feel like I can pretty much be myself at work,” 67 < α < .81, ICC = 0.52.

7.2.4. Relational energy

Relational energy was measured on a three-item scale developed by Boyatzis and Rochford (2020). The items were: “The relationships in my organization are a source of energy,” “The atmosphere in my organization is vibrant,” and “Interactions in my organization are lively,” .84 < α < .96, ICC = 0.61.

8. Results

8.1. Growth models

Table 1 presents the correlations between the variables at the level of the time-point (i.e., Level 1; nested within teachers) and at the teacher level (i.e., Level 2). Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for each variable across measurements. To obtain interpretable results for the intercept, the time of the first measurement was coded as zero. There were no variables with 5% or more missing values. Thus, there was no need to employ an imputation method for missing values.

Table 1. Correlations for variables at Levels 1 and 2

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Listening perception | (NA) | 0.43** | 0.42** | 0.46** |

| 2. Psychological safety | 0.55** | (NA) | 0.33** | 0.28** |

| 3. Autonomy | 0.70** | 0.50** | (NA) | 0.23** |

| 4. Relational energy | 0.41** | 0.32* | 0.52** | (NA) |

Note: Correlations above the diagonal are within-person (Level 1; person-centered), Ns = 278–293; correlations below the diagonal are between teachers (aggregated for each individual across measurements); N = 52; *p < .01, **p < .05.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the variables across the measurements

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Overall | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Listening perception | 6.21 | 1.23 | 6.6 | 1.31 | 6.81 | 1.13 | 7.05 | 0.97 | 7.15 | 1.23 | 7.45 | 0.88 | 6.86 | 1.29 |

| Psychological safety | 5.53 | 1.66 | 5.84 | 1.31 | 6.01 | 1.3 | 6.36 | 1.27 | 6.26 | 1.34 | 6.76 | 1.26 | 6.1 | 1.42 |

| Autonomy | 6.26 | 1.5 | 6.81 | 1.17 | 6.79 | 1.07 | 7.06 | 0.85 | 7.32 | 0.96 | 7.58 | 1.1 | 6.96 | 1.21 |

| Relational energy | 6.58 | 1.89 | 6.76 | 1.73 | 6.99 | 1.43 | 6.72 | 1.48S | 7.19 | 1.32 | 7.4 | 1.14 | 6.94 | 1.54 |

Note: Time 0: Baseline—before the listening education programs; Overall—the mean and standard deviation across all measurements.

We used random coefficient regression models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to examine the outcomes of the listening training program, with time as a fixed factor and random slopes and intercepts. This approach served to test growth curves (which were hypothesized to take the form of increases) in listening perception, psychological safety, autonomy, and relational energy as the teacher training progressed. This analytic approach also examined co-occurring changes among multiple outcomes and specifically examined covariations between listening perceptions and the theorized downstream outcomes.

The intercept and slope were allowed to vary based on the assumption that the covariance was not equal, hence requiring an unstructured covariance matrix. The unstructured matrix allows different variances along the matrix diagonal. The general equation for the Level 1 models was:

γti = π0i + π1iati + eti.

Where π0i represents the teachers' listening perceptions of how well their colleagues listened before the program (Time 0), π1i represents the average growth rate for teacher i throughout the training, and eti represents a random error. The general equations for the Level 2 models were:

π1i = β1i + r0i

π0i = β0i + r0i

Where β0i and β1i are the mean intercept and mean growth rates, respectively, and r0i and r1i are the Level 2 random effects, respectively, with the variances τ00 and τ11, and a covariance τ01 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

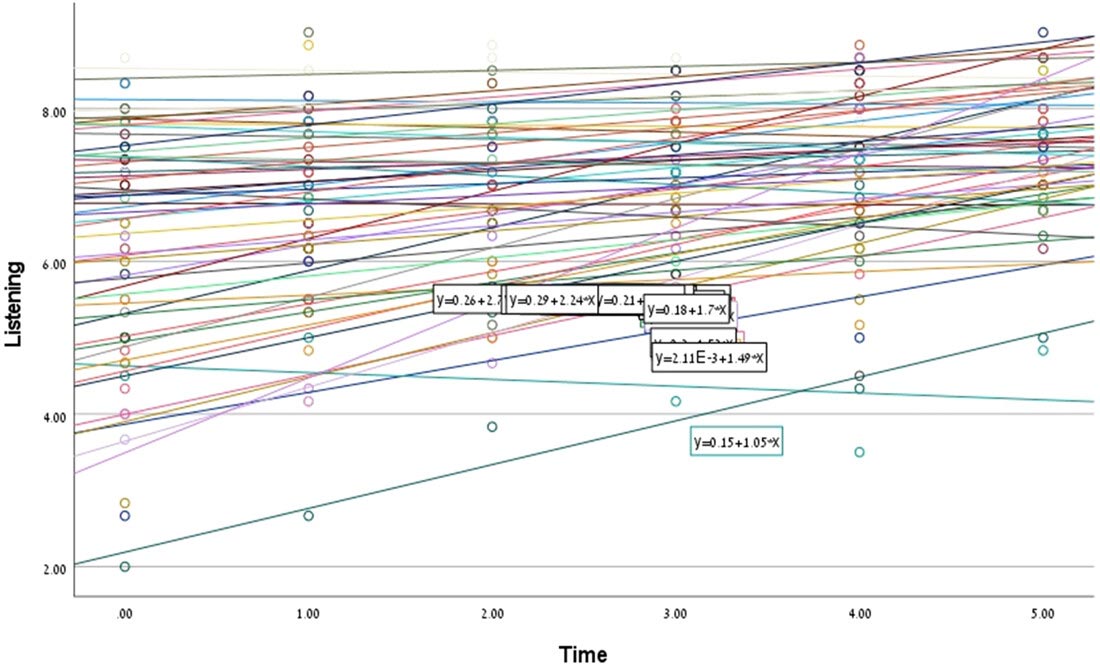

8.1.1. Listening perception

As shown in Table 3, the intercept for listening perception, which represents the level at the outset of the training (Time 0), was β⌃ = 6.31, which was above the midpoint of the scale. The teachers' listening perception of their colleagues increased significantly as the training program progressed, β⌃ = .22 SE = 0.03, t(52.24) = 6.56, p < .001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.16, 0.29]. That is, each training session increased the teachers' listening skills by an average of 0.22 points on the scale (see Figure 1).

Table 3. Random coefficient models

| Listening perception | Psychological safety | Autonomy | Relational energy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 6.31 | 0.2 | <.001 | 5.57 | 0.19 | <.001 | 6.34 | 0.19 | <.001 | 6.59 | 0.24 | <.001 |

| Time | 0.22 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.2 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.23 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.14 | 0.04 | =0.002 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Residual (σ2) | 0.35 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.74 | 0.08 | <.001 | 0.39 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.68 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| Intercept (1,1) | 1.95 | 0.42 | <.001 | 1.46 | 0.38 | <.001 | 1.59 | 0.36 | <.001 | 2.71 | 0.6 | <.001 |

| Slope (2,2) | 0.04 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.03 | 0.02 | =0.07 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.02 | =0.001 |

| Intercept slope (2,1) | −0.23 | 0.06 | <.001 | −0.11 | 0.06 | =0.08 | −0.21 | 0.06 | 0.004 | −0.32 | 0.1 | =0.001 |

Figure 1: Individual growth curves of listening perception throughout training

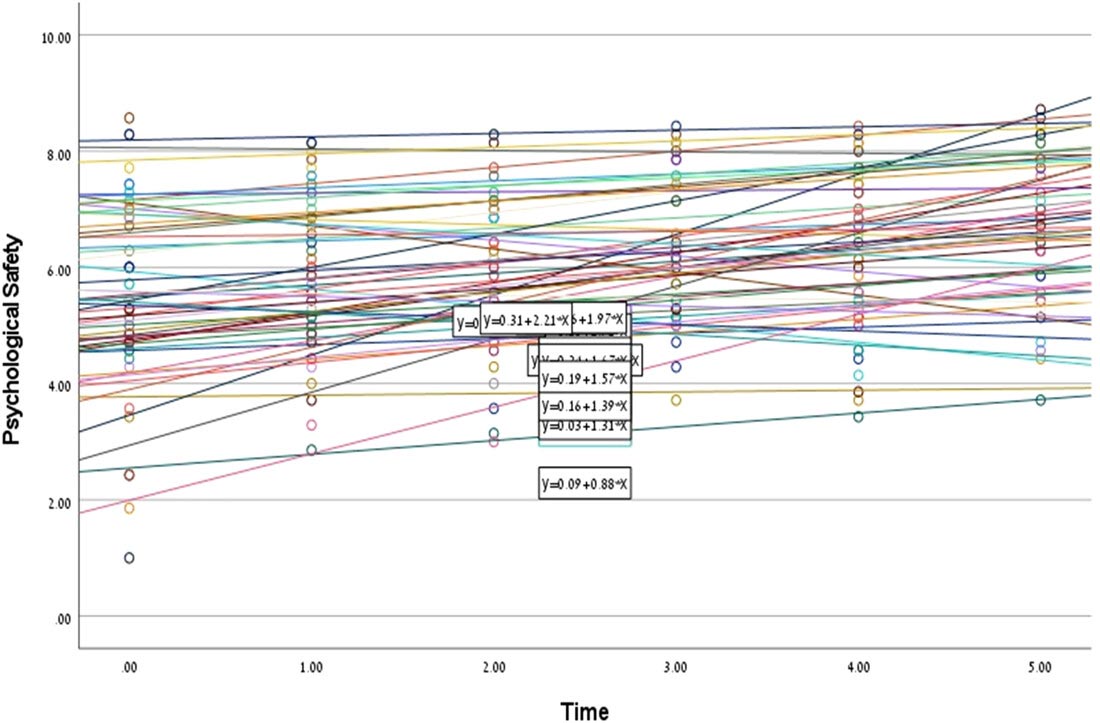

8.1.2. Psychological safety

The intercept of teachers' psychological safety was slightly above the scale's midpoint, β⌃ = 5.57. With regard to the growth trajectory, teachers' psychological safety showed a significant increase throughout training, β⌃ = .20, SE = 0.04, t(50.14) = 5.59, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.28]. Each training session increased the teachers' psychological safety by an average of 0.20 points on the scale (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Individual growth curves of psychological safety throughout training

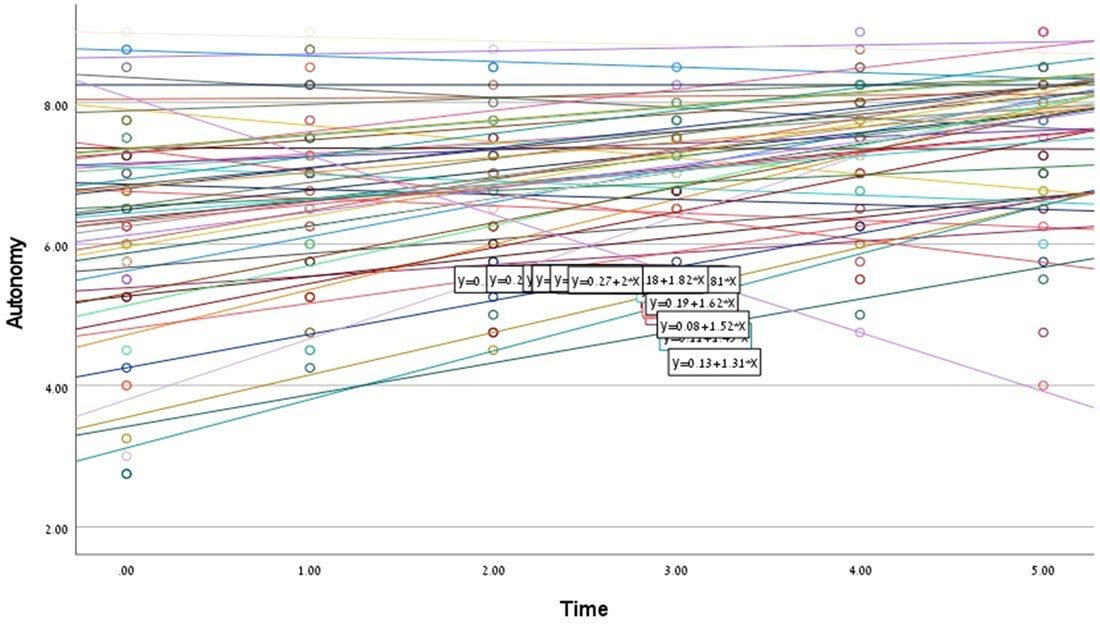

8.1.3. Autonomy need satisfaction

The intercept of teachers' autonomy need satisfaction was above the scale's midpoint, β⌃ = 6.40. With regard to the growth trajectory, the teachers' autonomy need satisfaction showed a significant increase over the course of the training, β⌃ = .23, SE = 0.04, t(49.64) = 6.52, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.15, 0.30]. That is, each training session increased the teachers' autonomy need satisfaction by an average of 0.23 points on the scale (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Individual growth curves of autonomy need satisfaction throughout training

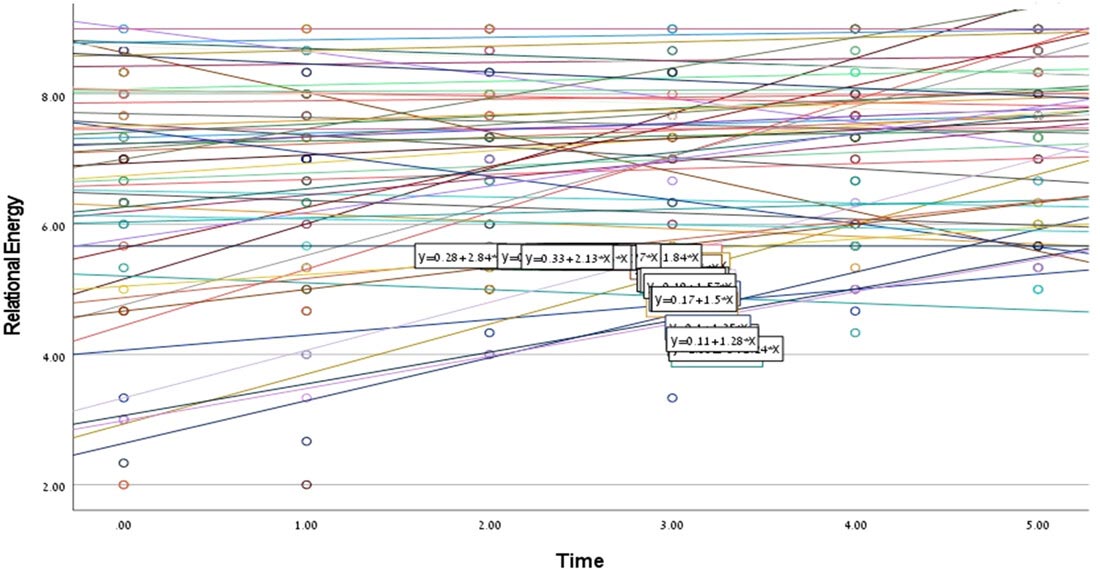

8.1.4. Relational energy

The intercept of teachers' relational energy was above the scale's mid-point, β⌃ = 6.59. The teachers reported a significant increase in relational energy, on average, throughout training, β⌃ = .14, SE = 0.04, t(52.41) = 3.29, p = .002, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.23]. Each training session increased the teachers' relational energy by an average of 0.14 points on the scale (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Individual growth curves of relational energy throughout training

Thus, the growth models lend weight to the research hypotheses. Specifically, the listening training program increased the teachers' listening skills, as rated by their colleagues, as well as their psychological safety, autonomy, and relational energy. As shown in Table 3, the variance of the intercepts and slopes of most variables (listening perception, autonomy, and relational energy) was significant. This suggests that the teachers differed in these constructs at the beginning of the training program, and more importantly, the growth trajectories differed between individuals.

8.2. Structural models

Table 4 presents the correlations between the latent slopes and intercepts of the teachers' listening perceptions with psychological safety, autonomy, and relational energy.

Table 4. Latent correlations of slopes and intercepts between listening perception and the dependent variables

| Listening perception | Psychological safety | Autonomy | Relational energy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent intercept | Latent slope | Latent intercept | Latent slope | Latent intercept | Latent slope | |

| Latent intercept | 0.77 (p < .001) | −0.10 (p = .436) | 0.82 (p < .001) | 0.08 (p = .767) | 0.63 (p < .001) | −0.11 (p = .53) |

| Latent slope | −0.61 (p = .002) | 0.64 (p < .001) | −0.43 (p = .039) | 0.84 (p = .026) | −0.15 (p = .38) | 0.67 (p = .009) |

The data were subjected to latent growth curve models to determine whether the growth in the outcome variables (H1b, H2b, and H3b) corresponded to the growth in the teachers' listening skills. The sample size was not large enough for a single model with listening perception and all three dependent variables. Hence, three models were run, where each model examined listening with a different dependent variable. Based on recommendations in Kline (2015), the residual covariates exceeding 0.10 were allowed to co-vary.

The latent correlation between the slope of listening perception and the slope of psychological safety was r = .64. This correlation was significant, p < .001, and suggests that an increase in the teachers' listening abilities was associated with increased psychological safety. The model had a good fit to the data: χ2(34) = 45.16, p = .095, CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.078, 90% CI = [0.00, 0.13].

The latent growth model of teachers' listening skills with autonomy is shown in Table 4, where the latent correlation between the slope of listening perception and the slope of psychological safety was r = .84. This correlation was significant, p = .026, which suggests that an increase in the teachers' perception of their colleagues' listening skills was associated with an increase in their own autonomy need satisfaction. The model fit the data well: χ2(49) = 65.56, p = .057, CFI = 0.979, RMSEA = 0.079, 90% CI = [0.00, 0.126].

Finally, the teachers' listening perception was also associated with their relational energy, as indicated by a significant positive latent correlation between the two slopes, r = .67, p < .001. This suggests that an increase in the teachers' perception of their colleagues' listening skills was associated with an increase in their own relational energy. The model fit the data well: χ2(51) = 59.37, p = .197, CFI = 0.989, RMSEA = 0.055, 90% CI = [0.00, 0.11].

Thus, overall, the multilevel models provided consistent support for the research hypotheses. Specifically, the listening training program increased the teachers' listening skills, as evidenced by their colleagues' perceptions. The training program also promoted the teachers' psychological safety (H1a), autonomy, need satisfaction (H2a), and relational energy (H3a). Furthermore, consistent with the hypotheses, the increase in listening perception was associated with the change in psychological safety, autonomy, and relational energy, respectively. These results provide support for the theoretical framework by suggesting that a better listening climate facilitated the program-induced outcomes.

9. General discussion

A year-long longitudinal study assessed growth in listening skills, psychological safety, autonomy, and relational energy of elementary school teachers who participated in a multi-session intensive listening training program. This program was designed to develop the teachers' capability to listen, fully and attentively, to others and one another by teaching these skills in conjunction with intensive experiential activities that practiced listening and provided a relational context where teachers could listen well to each other.

The findings taken repeatedly across six waves showed that participating in a group-based listening training program resulted in teachers' feelings that they had received high-quality listening from other teachers in their group. This perception increased linearly throughout training but perhaps more importantly, corresponded to further benefits as reported by teachers. Specifically, as training progressed, the teachers reported greater perceptions that other teachers supported them in their autonomy; in other words, they could express themselves and be freer to be themselves with other teachers and their superiors. In addition, the teachers reported that they felt more psychological safety, had the sense that they could take risks to share thoughts and feelings in a safe social environment, and had greater relational energy to take on these and other challenges. Consistent with expectations that experiencing good listening from colleagues would drive these benefits, the teachers' perceived listening co-occurred with these other changes as the training program unfolded.

The finding that a listening training program can increase psychological safety and autonomy need satisfaction by increasing the quality of perceived listening replicates and extends previous experimental studies linking listening perceptions to psychological safety (Castro et al., 2016, 2018; Itzchakov et al., 2016), autonomy need satisfaction in artificial settings (Weinstein et al., 2017), and psychological safety in cross-sectional field work (Castro et al., 2018). In the current study, laboratory-based manipulations of listening dyads were extended to explore this relationship in two new ways: (1) as a function of on-the-ground listening training that changed the relationships among a group of teachers who typically work together, (2) as a cumulative outcome across time as the teachers received additional training. This study is also the first to report the outcome of listening training on relational energy, which is important because they indicate that this type of program can foster a sense of vitality to engage in one's work (Baker, 2019; Owens et al., 2016). The findings thus contribute to the literature by showing that professional development, training, and support of educational staff are crucial in integrating listening skills in schools.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is also the first to examine listening training over time. To date, studies on listening training have either been laboratory experiments or-quasi field experiments or mostly employed pre-postmeasurements. Thus, the present study contributes to the growing body of research on workplace listening by showing that listening training can create more positive peer relationships in the workplace and directly benefit those employees who participate in it. In the future, special attention should also be paid to the training and support of school principals, supervisors, and other staff, to make them more aware of the importance and practical strategies of promoting listening skills within the school.

Another important direction is the need to envision ways to cultivate listening training sessions online, to scale up the process and allow more schools and students nationwide to benefit, as well as to model the ways teachers can implement these sessions online with their students; e.g., after school or during lockdowns. This may be challenging to implement during the COVID-19 crisis, and researchers could work toward a better understanding of how to implement online training for greater flexibility in terms of implementation.

The effective integration of listening practices in a given school should be done from a “whole school” perspective. There is a need to foster a climate and school culture of listening to cultivate listening effectively to become a way of life. This is because listening training is like physical exercise: to produce results, it needs to be done regularly, on the level of the educational staff and students. Further, listening is not an isolated skill that should be practiced separately from school life. Rather, it is essential to instill listening skills to allow teachers to experience listening integrally, which is necessary to build a positive work environment for teachers (Hinz et al., 2022), such as cultivating an openness to working in a culturally vibrant environment and with students from different cultures and backgrounds, promoting self-awareness, and coping with failures.

The present work has important implications for teachers' motivation and well-being. The Covid-19 pandemic had adverse effects on teachers' experiences in their workplace, reduced their well-being and motivation (e.g., McCallum, 2021; O'Brien et al., 2022), and increased their stress levels (Pellerone, 2021). The increase in relational energy observed across the training suggests that implementing listening training in schools, including virtual training (Itzchakov & Grau, 2020), might serve as a resource to maintain teachers' motivation during difficult times.

Furthermore, in many schools, due to various tensions, conflicts, and conflicting interests, teachers form rival groups with one another and the management. Such a negative school climate is associated with teachers who are afraid to speak their minds in certain contexts (Göksoy & Argon, 2016). It is also one reason that teaching is among the professions with the highest turnover rates (Ronfeldt et al., 2013); about one-third of the teachers leave within the first 5 years (e.g., Darling-Hammond & Sykes, 2003; Ingersoll, 2001). The increased psychological safety and autonomy associated with the training can help remedy the adverse effects of conflicts between the teaching staff and create a more unified and less divided workforce. When teachers learn how to listen well, their colleagues should feel that they can share their perspectives without being judged (psychological safety) and free to self-express (autonomy) in difficult conversations, facilitating more constructive disagreements and a social connection. This, in turn, can cultivate a positive school climate, which is increasingly recognized as an essential factor in creating safer, more supportive, and engaging K-12 schools (Thapa et al., 2013), as well as a sound strategy for preventing turnover (Dynarski, 2008).

9.1. Limitations and future research

The findings reported above should be considered in light of several methodological limitations. First, it was not possible to set up a control group. Thus, no causal conclusions can be drawn from the data because it was impossible to determine which changes occurred as a unique function of the listening training program. For example, it could be claimed that the listening-induced outcomes on some outcomes were because the teachers spent time socializing rather than improving their listening skills. Although the design cannot directly refute this possibility, this alternative explanation does not seem plausible because the teachers in both schools who participated in the training course had worked with one another for years and therefore had already had numerous opportunities to spend time together. Nevertheless, future research should include a control group to increase internal validity. This control group could be a school assigned to a waiting list or, better yet, teachers who receive a different kind of training. Another methodological limitation might be using only self-reports to assess the dependent variables. Although common in longitudinal designs, self-reports might raise social desirability concerns among participants.

Despite these limitations, previous laboratory experiments that have manipulated listening behavior have found that listening has a causal effect on increased psychological safety (Castro et al., 2016, 2018) and autonomy (Itzchakov & Weinstein, 2021; Itzchakov et al., 2022; Weinstein et al., 2021), suggesting that there is indeed a causal link between listening and these relational experiences which the current study was able to identify through an in-depth workplace training program delivered across a substantial span of time.

An important avenue for future research would be to determine whether the training has a carry-over effect, despite the encouraging results described here. The critical unanswered question is whether attendees serve as social agents who influence their social environments positively. In the case of the present study, do the pupils of the teachers or their parents observe changes in the teachers' listening skills? Put differently, does listening training affect people who did not participate but have work or social relationships with the attendees? Although not easy to examine, this question should be studied in future research to further explore the value of listening training programs in schools and organizations.

The present study replicates previous work that found that being listened to increases speakers' psychological safety (Castro et al., 2016, 2018; Itzchakov et al., 2016) and autonomy (Itzchakov & Weinstein, 2021; Itzchakov et al., 2022; Weinstein et al., 2021). Yet, the question of whether it increases these states for listeners is unexplored. Theoretically, because listening is a reciprocated process between the listener and the speaker (Kluger et al., 2021), it makes sense to assume that listeners would also benefit from it. However, it remains an open question because much less is known about listeners' effects than speakers' effects (Kluger & Itzchakov, 2022).

Finally, future research should examine whether similar effects on teachers emerge when their school principals undergo listening training and shape the climate in their organization (Thapa et al., 2013). Such work would also address an important gap in the listening training literature that mainly focused on employees and largely neglected training for managers with a few exceptions (e.g., Kubota et al., 2004).

10. Conclusion

The present study examined teachers who participated in a group listening training program over an entire school year. It showed that the training promoted teachers' autonomy, psychological safety, and relational energy growth. These benefits accrued linearly over time and with cumulative training sessions and coincided with increased perceived listening from other attendees. In short, the findings provide evidence that listening training generated more positive relational experiences for the attendees.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant #460/18 from the Israel Science Foundation to Prof. Guy Itzchakov.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Alzamil, J. (2021). Listening skills: Important but difficult to learn. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 12, 366–374.

- Baker, W. E. (2019). Emotional energy, relational energy, and organizational energy: Toward a multilevel model. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 373–395.

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 941–952.

- Bensing, J. M., & Sluijs, E. M. (1985). Evaluation of an interview training course for general practitioners. Social science & medicine (1982), 20, 737–744.

- Bodie, G., Fitch-Hauser, M., & Powers, W. (2011). Teaching Social Skills. In Instructional Design: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools and Applications (pp. 1689–1713). IGI Global.

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods. Guilford.

- Boyatzis, R., Smith, M. L., & Van Oosten, E. (2019). Helping people change: Coaching with compassion for lifelong learning and growth. Harvard Business Press.

- Boyatzis, R. E., & Rochford, K. (2020). Relational climate in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00085

- Castro, D. R., Anseel, F., Kluger, A. N., Lloyd, K. J., & Turjeman-Levi, Y. (2018). Mere listening effect on creativity and the mediating role of psychological safety. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 12, 489–502.

- Castro, D. R., Kluger, A. N., & Itzchakov, G. (2016). Does avoidance-attachment style attenuate the benefits of being listened to? European Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 762–775.

- Čepić, R., Vorkapić, S. T., & Šimunić, Z. (2018). Autonomy and readiness for professional development: How do preschool teachers perceive them? In L. G. Chova, A. López Martinez, & I. Candel Torres (Eds.), EDULEARN18 Proceedings (pp. 1319–1327). Palma de Mallorca, Spain: IATED Academy.

- Cojuharenco, I., & Karelaia, N. (2020). When leaders ask questions: Can humility premiums buffer the effects of competence penalties? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 156, 113–134.

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers' psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000088

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. Available online from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Educating_Whole_Child_REPORT.pdf

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Sykes, G. (2003). Wanted, a national teacher supply policy for education: The right way to meet the “highly qualified teacher” challenge. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11, 33.

- De Lucio, L. G., Lopez, F. J. G., Lopez, M. T. M., Hesse, B. M., & Vaz, M. D. C. (2000). Training programme in techniques of self-control and communication skills to improve nurses' relationships with relatives of seriously ill patients: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 425–431.

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43.

- Dikilitaş, K., Griffiths, C., & Tajeddin, Z. (2020). Teacher autonomy and good language teachers. Lessons from good language teachers, 54–66.

- Doerr, H. M. (2006). Teachers' ways of listening and responding to students' emerging mathematical models. ZDM, 38, 255–268.

- Dynarski, M. (2008). Dropout Prevention IES PRACTICE GUIDE.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23–43.

- Edwards, N., Peterson, W. E., & Davies, B. L. (2006). Evaluation of a multiple component intervention to support the implementation of a ‘therapeutic relationships’ best practice guideline on nurses' communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling, 63, 3–11.

- Endrejat, P. C., Klonek, F. E., Müller-Frommeyer, L. C., & Kauffeld, S. (2021). Turning change resistance into readiness: How change agents' communication shapes recipient reactions. European Management Journal, 39, 595–604.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

- Fernandes, P. R. S., Jardim, J., & Lopes, M. C. S. (2021). The soft skills of special education teachers: Evidence from the literature. Education Sciences, 11, 125. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/11/3/125

- Gilbert, M. B. (1988). Listening in school: I know you can hear me—but are you listening? International Listening Association, 2, 121–132.

- Göksoy, S., & Argon, T. (2016). Conflicts at schools and their impact on teachers. Journal of Education and Training studies, 4, 197–205.

- Greenglass, E. R., Fiksenbaum, L., & Burke, R. J. (2020). The relationship between social support and burnout over time in teachers In Occupational Stress (pp. 239–248). CRC Press.

- Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20, 90–100.

- Hinz, J., Stephens, J. P., & Van Oosten, E. B. (2022). Toward a pedagogy of connection: A critical view of being relational in listening. Management Learning, 53, 76–97.

- Hughes, S., & Lewis, H. (2020). Tensions in current curriculum reform and the development of teachers' professional autonomy. The Curriculum Journal, 31, 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.25

- Hunter, E. M., & Wu, C. (2016). Give me a better break: Choosing workday break activities to maximize resource recovery. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000045

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 499–534. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038003499

- Itzchakov, G. (2020). Can listening training empower service employees? The mediating roles of anxiety and perspective-taking. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29, 938–952.

- Itzchakov, G., Castro, D. R., & Kluger, A. N. (2016). If you want people to listen to you, tell a story. International Journal of Listening, 30, 120–133.

- Itzchakov, G., & DeMarree, K. G. (2022). Attitudes in an interpersonal context: Psychological safety as a route to attitude change. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 4242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.932413

- Itzchakov, G., DeMarree, K. G., Kluger, A. N., & Turjeman-Levi, Y. (2018). The listener sets the tone: High-quality listening increases attitude clarity and behavior-intention consequences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44, 762–778.

- Itzchakov, G., & Grau, J. (2022). High-quality listening in the age of COVID-19. Organizational Dynamics, 51, 100820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100820