- Sections

- Figures

- Tables

- References

- Açıkgöz, A., & Günsel, A. (2011). The effects of organizational climate on team innovativeness. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 920-927. Google Scholar Crossref

- Constantin, T. (2008). Analiza climatului organizaţional. Psihologie organizaţional-managerială. Tendinţe actuale. Polirom (Organizational climate analysis. Organizational-managerial psychology. Recent trends. Polirom).

- Constantin, T. (2009). The value of organizational climate analysis in preventing and solving professional environment conflicts. In C. Ticu, & A. Stoica-constantin, Conflict, Change, and Organizational Health (pp. 13-27). Iaşi: Universit ii, Alexandru Ioan Cuza”.

- Ehrhart, M. G., Schneider, B., & Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture: An introduction to theory, research, and practice. Routledge.

- Felner, R. D., Favazza, A., Shim, M., Brand, S., Gu, K., & Noonan, N. (2001). Whole school improvement and restructuring as prevention and promotion: Lessons from STEP and the Project on High Performance Learning Communities. Journal of School Psychology, 39(2), 177-202.

- Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., & Smith, D. B. (2004). Leaders, values, and organizational climate: Examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. Journal of business ethics, 55(3), 223-241.

- Guion, R. M. (1973). A note on organizational climate. Organizational behavior and human performance, 9(1), 120-125. Google Scholar Crossref

- Halpin, A. W., & Croft, D. B. (1963). Organisational Climate of Schools (Midwest Administration Center, University of Chicago). Halpin Organisational Climate of Schools 1963.

- Hellriegel, D., & Slocum Jr, J. W. (1974). Organizational climate: Measures, research and contingencies. Academy of management Journal, 17(2), 255-280. Google Scholar Crossref

- Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. The Journal of school health, 74(7), 274. Google Scholar Crossref

- Misnawati, T. (2020). School Climate Contribution as an Intermediary Variable to Teacher’s Work Through Work Motivation and Satisfaction. Journal of K6 Education and Management, 3(2), 128-137.

- Paterson, J. N., & Hartel, C. E. (2002). An integrated affective and cognitive model to explain employees’ responses to downsizing. In N. M. Ashkanasy, W. J. Zerbe, & C. E. Härtel, Managing emotions in the workplace (pp. 25-44). M.E Sharpe, Inc.

- Reichers, A. E., & Schneider, B. (1990). Climate and culture: An evolution of constructs. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 5–39). Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vol. 2). John Wiley & Sons.

- Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., & Macey, W. H. (2011). Perspectives on organizational climate and culture. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 1. Building and developing the organization (pp. 373–414). American Psychological Association.

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of educational research, 83(3), 357-385. Google Scholar Crossref

- Zohar, D., & Hofmann, D. A. (2012). Organizational climate and culture. The Oxford handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar Crossref

Abstract

The organizational climate of educational institutions is increasingly recognized as a significant factor in the analysis of an educational institution’s effectiveness and its ability to achieve its goals, especially in today’s volatile and challenging reality. Researchers and practitioners have identified a need to develop tools utilizing a holistic approach to organizational climate assessment. One such tool is the “ECO system” (Evaluation Climate Organizations), which was developed in Europe for use in security and business organizations. The ECO system analyzes various factors comprising the organizational climate, from the perspective of the individual, the work team, and the entire organization. Regrettably, its reliability has not yet been tested in Israel or elsewhere among educational organizations. This article examines the characteristics of the ECO system in nine independent formal and informal educational organizations in Israel and the validity and reliability of the tool’s Hebrew version. Three hundred twenty-two educators from six formal and three informal educational organizations were sampled. The findings indicate that the ECO system questionnaires are reliable and can assist managers to obtain a clear picture of the climate prevailing in their organizations and enhance their ability to identify opportunities for navigating change and crisis in their organization.

Keywords: Educational organizations, ECO system questionnaire, organizational climate

Introduction

The early students of organizational climate were psychologists who viewed the climate as the "personality" or the "atmosphere" of the organization. They viewed the workplace, where the employee spends long hours in contact with co-workers—be they colleagues, superiors, or subordinates—as a significant social environment. Co-workers influence the employee’s job satisfaction, the quality of the work, the physical work- environment, and more. Over the years, many researchers from fields such as social psychology, organizational psychology, sociology, and organization management, have described the work environment in bureaucratic, industrial, and educational organizations and have agreed to the term "organizational climate" (Schein, 2010).

A few core assumptions underpin the contemporary understanding of organizational climate. First, climate is an outcome of organizational characteristics such as leadership, communication, policy. Second, climate is not a direct outcome of those organizational characteristics but the product of the employees’ perception of their experience in it and the meaning given to them. This means that the climate does not come to describe the organization's policies, customs, occupations, and procedures; rather climate-descriptors are used to explore the psychological meaning they produce in employees (Reichers & Schneider, 1990). Third, organizational climate is an abstract description of human experience in the work environment and the meaning adhered to those experiences. As such, it does not relate to the individual but rather to the experiences shared by members of an organizational unit or group and the meaning attributed to them. The shared experiences are reflected by interactions within the unit, or organization (Ehrhart et al., 2013).

The organizational climate may be defined as repetitive patterns, behaviors, opinions, values, and feelings that characterize the work in the organization. These perceptions constitute the meanings given to the policies and work processes in the organization (Schneider et al., 2011). The determination of an organization’s climate contributes to an understanding of the current “mood” of the team—revealing both the effects of recent organizational changes and anticipated employee behavior over time (Constantin, 2008). Another widely accepted definition that is found in the literature views organizational climate as a perception of the nature of the relationship between the organization and its employees based on elements like repetitive behavior patterns, opinions, values, and emotions that characterize work in the organization (Zohar & Hofmann, 2012).

In conclusion, the organizational climate influences productivity, burnout, motivation, and employee behavior. The assessment of organizational climate analysis provides an accurate diagnosis of factors related to overcoming changes, crises, conflicts, and uncertainty conflicts in the organization; relevant attention to employee well-being; obtaining critical information for navigating the organization during times of crisis; and planning, and managing organizational change (Constantin, 2009).

Organizational Climate Measurements and Analysis in Educational Organizations

Educational organizations' climate is a heterogeneous concept that relates to a set of measures that characterize the experience of the school community (students, staff, and student families), considering relationships, lifestyles, norms, values, teaching, learning, school leadership, and organizational structure (Libbey, 2004). Halpin and Croft (1963) were among the pioneers in the field of school climate. According to them, climate is a general idea that reflects the atmosphere in educational organizations: the climate is experienced by the staff and reflects the collective perception of school routines and influences their attitudes and behavior.

The way the school climate is defined has implications for the tools with which the climate will be measured. Nevertheless, there is no consensus on the definitions of the school climate, healthy and optimal climate, or the necessary school climate change processes. Similarly, there is no consensus regarding the metrics that need to be regularly reviewed in order to assess and refine the improvement efforts (Thapa et al., 2013). Despite the heterogeneity and variety of metrics currently available to describe the school climate, there is no doubt in the eyes of researchers that there is importance in improving measurement methods due to the significant impact of the school climate as supporting or undermining learning ability and schoolwork quality. Felner et al. (2001) argued that efforts to bring about change in educational organizations, should be implemented comprehensively, from management to employees through the organizational climate. An organizational climate which is properly managed helps at the individual level to academic success and promoting a wide range of developmental abilities. At the community level prevent social-emotional, behavioral difficulties and lead to the strengthening of social resilience (Felner et al., 2001).

The organizational climate construct assumes that individuals within a given subsystem or organization should have similar perceptions about the climate. A specific concern with subjective climate measurements, contrary to objective ones, is that climates can be as numerous as the amount of organization members. However, research into such climates state that consistency cannot be secured via a process represented by discerning averages in extreme individual differences (Hellriegel & Slocum, 1974). However, there is a broad unanimity among analysts that the organizational climate influences productivity, weariness, motivation, and employee conduct (Ehrhart et al., 2013). Organizational climate analysis reveals accurately the factors related to crisis and conflicts in the organization, relevant reference to employee well-being, learning strategic information for navigating the organization in crisis, planning, and implementing organizational change (Paterson & Hartel, 2002). The identification of important organizational climate elements and the design of standardized metrics for their measurement would be beneficial to any business dealing with organizational consulting (Constantin, 2009) and will contribute greatly to the leaders of the education systems.

Problem Statement

- A basic question that arises in researching the organizational climate of education enterprises relates to the manner by which the teachers’ perceptions of climate can be measured.

- The ECO system questionnaire (Evaluation Climate Organizations) is being used to assess various dimensions of the organizational climate, but until now its validity and reliability have not been examined among educational organizations in particular and in Israel in general.

Research Questions

Examines the characteristics of the organizational climate and the diagnostic tool: the ECO system.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this study is to examine the psychometric properties of the ECO system in nine independent samples of educational organizations in Israel, including elementary school, high school, and in an informal education setting. In total, 322 educators completed the ECO system questionnaire. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and correlation tests were assessed for the samples.

Research Methods

The ECO System (Evaluation Climate Organizations) Questionnaire (Constantin, 2009). The questionnaire provides a comprehensive assessment of the organization’s various climate dimensions. Specifically, the ECO questionnaire assesses 14 dimensions of organizational climate with eight statements for each dimension. The statements describe behaviors and attitudes regarding the organization’s activities and are classified by the following dimensions:

- Task: the manner of defining tasks and objectives, both for the organization as a whole, and for each employee (α = .76).

- Relationships: the quality of the relationships between the employees in the context of professional communication and collaboration, and of maintaining a non-conflict climate (positive interpersonal relationships) (α = .88).

- Motivation: the motivational system in the organization, supported by penalties, recognition of merits, promotion opportunities, and training (incentive motivation) (α = .77).

- Support: the resources, the work conditions and the incentives provided by the organization to employees, to enable them to perform their responsibilities (support for performance), (α = .62).

- Leadership: the effectiveness of the leadership style: effective, by supporting individual and collective performance, by ensuring conditions for efficiency, etc. (efficient leadership), (α = .63).

- Evaluation: the evaluation (official or unofficial) of the employees’ activity, based on clear objectives and criteria, and offering feedback and solutions in order to improve work (objective assessment), (α = .70).

- Justice: the suitability of the decisions in the organization regarding the allocation of tasks and resources, and the fairness of the way in which the employees are treated or rewarded for their work (organizational equity), (α = .49).

- Attachment: the degree of identification with the company, the extent to which employees share the goals and values of the company/institution, identify with its future, are loyal and interested in the welfare of the organization (firm identification), (α = .84).

- Decisions: the autonomy of employees when deciding how to do their job or the extent to which they are consulted when important decisions are being taken (decision quality), (α = .54).

- Learning: the conditions and the climate that allow for the acquisition of new information, experimentation and putting into practice valuable ideas (organizational learning), (α = .75).

- Satisfaction: the degree of contentment with the nature and importance of the work, the level of freedom of action, the recognition and support received (stimulating activity), (α = .71).

- Safety: the sense of security and certainty about remuneration, work organization, relationships with others, confidence in the future of work (occupational safety), (α = .55).

- Communication: the quality of formal communication procedures, involvement in decision making and in defining tasks, rules, and informal communication climate (effective communication), (α = .65).

- Overload: any work done in excess or the feeling that the nature, volume, and diversity of tasks exceed the ability to cope (work overload), (α = .61).

Each statement is ranked on a five-point Likert type scale (1 = Very little, 2 = little, 3 = medium, 4 = high, 5= very high).

Organizational climate functionality areas

The ECO System provides relevant graphical charts and analyses of each organizational climate factor, outlining its impact on individual and global performance levels. Four different “organizational climate functionality areas” are considered: dysfunctional, deficient, functional, and successful. They are described, as follows:

- Successful/Performant climate – the factors are assessed by staff as extremely positive. This area describes an ideal situation for an organization. Institutions with an organizational climate in this area ensure optimal productivity and efficiency, but it will be rare to find many organizations in this area.

- Functional climate – in this area the factors received a positive assessment mostly, though not entirely, satisfactory. Organizations that have such a climate are functional and work well. The climate contributes positively to the organization's activities, however there is room to strive and improve.

- Deficient climate – this area includes factors that have apparently been neglected by the organization and are perceived by employees as adversely affecting the individual level and the organization level, harming efficiency, and creating problems. It is imperative for organizations in this area to respond to this alert and to intervene quickly in order to move the factors that are lacking to the functional area.

- Dysfunctional climate – institutions in this area received extremely negative responses, indicating a pervasive dysfunction that can lead to an organization-wide crisis. It is therefore highly advisable to take steps to avoid this situation as it affects the professional activity both at the individual level and at the level of the entire organization.

Findings

Descriptive statistical tests were performed on the data collected from the entire sample (N = 322). The means and standard deviations for each component in the questionnaire were determined (Table 1). Particularly notable was the ECO Relationship component with an average of 3.83, a standard deviation of 0.72 and a reliability of .85. Additional indices that received a high score were the ECO Management (mean = 3.79), ECO Identification (mean = 3.95), ECO Satisfaction (mean = 4.12), ECO overcharge (mean = 3.91), ECO safety (mean = 3.95). ECO Justice and ECO safety were found with reliability relatively low compared to the rest (α = 0.50), this result can be explained since education organizations as part of a public system under regulation, fixed wage agreements, and a seniority mechanism that does not allow dismissal easily and other characteristics that make the above criteria less relevant. Another important finding for confirming the questionnaire is that all variables used in the research (except for gender, nationality/native language, or professional status) are continuously variable. In addition, they have a normal distribution, so we could use linear regression. The dimensions of the ECO showed sufficient reliability where all but one dimension exceeded α > 0.7.

Next, the correlations among the different dimensions of the ECO were examined, with several dimensions showing high correlation scores (defined as: -0.5 < r > 0.5). For example, the dimension of ECO Relationship was strongly correlated with the dimension ECO Identification, r = .70, p < .05. There were strong correlations between the dimensions of ECO Motivation and ECO Learning, r = .74, p < .05. and between the dimensions of ECO Support and the dimension of ECO Motivation, r = .72, p < .05. A distinctly strong positive correlation is found between the above. That is, ECO relationships for example positively affect the ECO components of motivation, support, management, organizational justice, identification, and learning in the organization.

Psychometric Characteristics of ECO System Questionnaire

Table 1 - Descriptive statistics. N = 322

| M | SD | Cronbach's α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECO Task | 3.35 | 0.55 | 0.76 |

| ECO Relationship | 3.83 | 0.72 | 0.85 |

| ECO Motivation | 3.35 | 0.6 | 0.74 |

| ECO Support | 3.31 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| ECO Management | 3.79 | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| ECO Evaluation | 3.02 | 0.56 | 0.7 |

| ECO Justice | 3.4 | 0.41 | 0.45 |

| ECO Identification | 3.95 | 0.62 | 0.82 |

| ECO Decision | 3.51 | 0.36 | 0.54 |

| ECO Learning | 3.64 | 0.61 | 0.75 |

| ECO Satisfaction | 4.12 | 0.52 | 0.71 |

| ECO Overcharge | 3.91 | 0.43 | 0.49 |

| ECO Safety | 3.95 | 0.62 | 0.46 |

| ECO Communication | 3.28 | 0.48 | 0.65 |

We can see in Table 1 of all the statements in the questionnaire, the statement that received the highest score is in the context of the relationship dimension in the organization: The quality of the relationships between the employees in this organization affects the quality of my work positively or negatively.

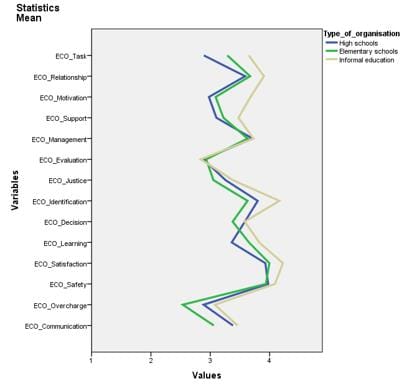

Comparison between Types of Organizations

When comparing between groups a one-way ANOVA test shows that in the climate variables of management and evaluation, there are no differences at all between high schools, elementary schools, and informal educational organization. In all the other indices, despite statistical differences among the three types of organizations, in general they are small and not meaningful. The table shows a high sum of squares in ECO Task (sum Between Groups = 29.468) and ECO Identification (sum Between Groups = 15.689), and the lowest score at factors ECO Management (sum Between Groups = .600) and ECO Evaluation (sum Between Groups = .449). We can see in the graph the limited skew of the scores by organizational type. In general, all the average climate indices in informal education organizations were rated higher than in formal education.

Figure 1: Comparison between Types of Organizations – One-way ANOVA.

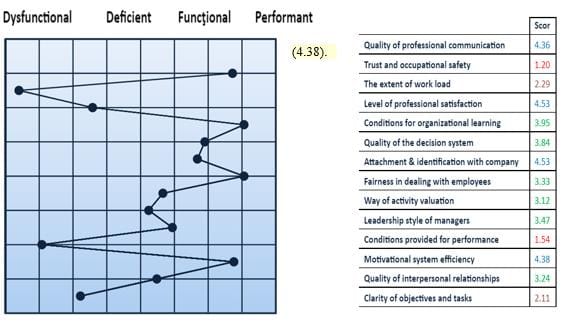

Organizational climate Factors and Scores

describes the climate factors and scores by functionality areas. The chart discovers that most, if not all, of the characteristics of the organizational climate in High School #1, which does not have social intervention programs, are, according to ECO systems analysis, dysfunctional. The Dysfunctional climate zone indicates the worst organizational climate situation. The Deficient Climate area contains factors which the personnel see as lacking attention and in need of improvement. ECO Motivation, ECO Justice, and ECO Identification are in deficient area.

Figure 2: Organizational climate Factors and Scores

Figure 3: High School #1 (n=34). No Practical Social Policies and Programs

The Performant Climate zone is the area that describes an ideal situation for a firm, wherein the staff assessment of the factors being analyzed is extremely positive. In the Functional Climate zone factors are assessed as predominantly positive, although the situation is not entirely satisfactory. High School 3 in which social programs and interventions for professional development and emotional discourse are implemented, shows scores vastly differently from High School 1. Dimensions of organizational climate are situated in all four regions of the continuum, from dysfunctional to optimal functioning. Most of the rankings are in the functional to optimal area, the highest scores are of ECO Relationship (4.36), ECO Satisfaction (4.53), ECO Identification (4.53), and ECO Motivation (4.38).

Figure 4: Organizational Climate Factors and Scores

High School 3 (n=38). Practical Social Policies and Programs are Implemented.

Conclusion

Organizational climate is considered one of the factors influencing the success of an organization. Educational institutions are facing a period of great change requiring school principals to navigate prudently in the face of many different challenges. A tool that can assess the overall organizational climate, and evaluate its various components, map the dimensions that require improvement, and highlight the inhibiting and enriching forces in the organization, can help school heads to lead their institutions to an optimal organizational climate. Organizational climate is a transient and changeable quality comprising attributes such as repeated behavior patterns, opinions, and feelings that are easily influenced by the contemporaneous environment and conditions. The organizational climate is expressed through concrete, observable, and identifiable behaviors that can be assessed at any time based on the subjective perceptions of those involved. As a result, it is possible to extract practical information for improving the organizational climate from an analysis of it.

Our research shows for the first time that the Israeli version of the ECO questionnaire has adequate psychometric properties across a broad sample of educators. The ECO system can provide relevant information to characterize the organizational climate, sort out the more challenging elements and plan interventions in educational organizations.

The analysis of data from the ECO questionnaire regarding the existing organizational climate, as perceived by all of those surveyed from all the participating educational organizations, shows that the most significant components of the ECO questionnaire were: relationships, identification and satisfaction. This outcome matches research claims that to the extent that significant quality relations exist between teachers and administration and among the teachers, themselves, teachers will express a high degree of identification with the school and commitment to the teaching profession. Quality relations among school personnel are those that encompass cooperation, involvement in decision-making, sensitivity, and empowerment.

Educators consider the relationship component to have a notable positive or negative effect on the organizational climate. Understanding the influence of people who surround the employee at work and the employee's feelings about their job, is vital considering that the workplace becomes a significant social environment (Misnawati, 2020).

Examination of the differential ranking of constituent components of the organizational climate in the different settings under study reveals that the differences are small and insignificant (Figure 1). However, it was found that the components of identification with the organization and job satisfaction were higher in informal education organizations. This could be because most educators in this sector grow into the organization by first being a member of a youth group and subsequently deciding to become educators and managers in the informal organization.

The ECO questionnaire allows for a wide variety of cross-sectional analyses which can help managers to find and manage particular challenges to the school climate. A comparison of perceptions according to management position showed a significant difference between schools engaged in social policies and programs as opposed to those without such programs. The literature suggests that when teachers feel supported both by the principal and by their peers, they are more committed to the profession (Guion, 1973). Schools where there are good social ties between members of the school community, are likely to be those who perform more vigorously (Açıkgöz & Günsel, 2011). This, in turn, improves student achievement, due, in part, to the improvement of the school climate. In addition, leadership styles have an enormous influence on the social climate (Grojean et al., 2004). All the above shows how essential it is for a manager to understand the feeling of the staff about the organization, and work on his own style of leadership, according to the conclusions he can find by using the ECO questionnaire.

The ECO Questionnaire in this research was executed a short time before humanity faced the crisis of Covid-19 which affected the educational system most vigorously. Organizational climate analysis provides an accurate diagnosis of factors related to crises and conflicts in the organization, relevant reference to employee well-being, learning strategic information for navigating the organization in crisis, planning, and administering organizational changes. Therefore, we suggest further research with the aim to improve organizational climate by using the questionnaire and developing strategies to improve organizational climate in educational organizations of all kinds.

Recommendations

Results and analysis of the ECO questionnaire allow the managers of the organizations to diagnose the state of the organization and identify the indicators in which there is room for improvement. In this way, it is possible to move effectively from the current situation to the desired situation, to improve the well-being of employees and the efficiency of the entire organization. It is recommended that the directors of educational institutions. 1) diagnose their organization with the help of the ECO questionnaire. 2) Work to strengthen the ties between employees and the various departments as well as improve interpersonal communication. 3) Create norms of collaboration in decision making and tackling challenges and thus strengthen organizational identification.

References

- Açıkgöz, A., & Günsel, A. (2011). The effects of organizational climate on team innovativeness. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 920-927.

Constantin, T. (2008). Analiza climatului organizaţional. Psihologie organizaţional-managerială. Tendinţe actuale. Polirom (Organizational climate analysis. Organizational-managerial psychology. Recent trends. Polirom).

- Constantin, T. (2009). The value of organizational climate analysis in preventing and solving professional environment conflicts. In C. Ticu, & A. Stoica-constantin, Conflict, Change, and Organizational Health (pp. 13-27). Iaşi: Universit ii, Alexandru Ioan Cuza”.

Ehrhart, M. G., Schneider, B., & Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture: An introduction to theory, research, and practice. Routledge.

Felner, R. D., Favazza, A., Shim, M., Brand, S., Gu, K., & Noonan, N. (2001). Whole school improvement and restructuring as prevention and promotion: Lessons from STEP and the Project on High Performance Learning Communities. Journal of School Psychology, 39(2), 177-202.

Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., & Smith, D. B. (2004). Leaders, values, and organizational climate: Examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. Journal of business ethics, 55(3), 223-241.

Guion, R. M. (1973). A note on organizational climate. Organizational behavior and human performance, 9(1), 120-125.

Halpin, A. W., & Croft, D. B. (1963). Organisational Climate of Schools (Midwest Administration Center, University of Chicago). Halpin Organisational Climate of Schools 1963.

Hellriegel, D., & Slocum Jr, J. W. (1974). Organizational climate: Measures, research and contingencies. Academy of management Journal, 17(2), 255-280.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. The Journal of school health, 74(7), 274.

- Misnawati, T. (2020). School Climate Contribution as an Intermediary Variable to Teacher’s Work Through Work Motivation and Satisfaction. Journal of K6 Education and Management, 3(2), 128-137.

Paterson, J. N., & Hartel, C. E. (2002). An integrated affective and cognitive model to explain employees’ responses to downsizing. In N. M. Ashkanasy, W. J. Zerbe, & C. E. Härtel, Managing emotions in the workplace (pp. 25-44). M.E Sharpe, Inc.

Reichers, A. E., & Schneider, B. (1990). Climate and culture: An evolution of constructs. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 5–39). Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (Vol. 2). John Wiley & Sons.

- Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., & Macey, W. H. (2011). Perspectives on organizational climate and culture. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 1. Building and developing the organization (pp. 373–414). American Psychological Association.

Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of educational research, 83(3), 357-385.

- Zohar, D., & Hofmann, D. A. (2012). Organizational climate and culture. The Oxford handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Citation: Yomtovian, A., & Constantin, T. (2022). Psychometric Characteristics Of The Organizational Climate In Israeli Educational Organizations. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 138-148). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.13

Copyright: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.